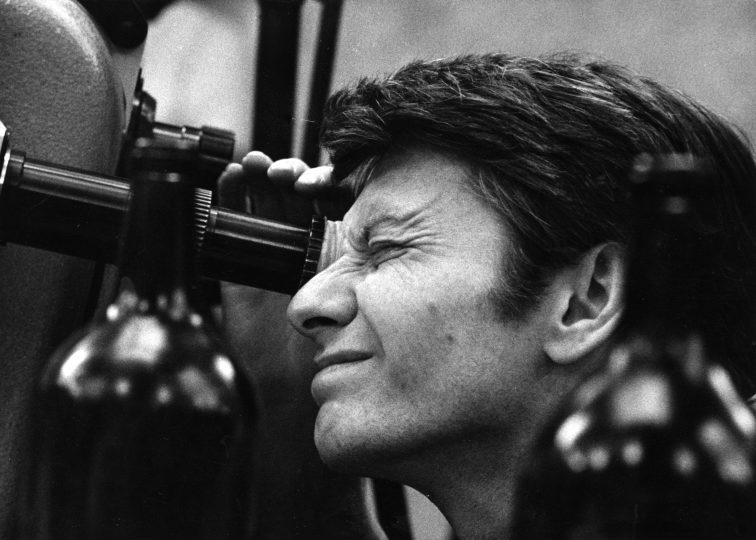

Jaroslav Kučera (August 6, 1929 – January 11, 1991) came from a civil servant’s family. After his graduation from secondary school (1948), he enrolled at the newly founded Faculty of Performing Arts (AMU) in Prague as a student in film photography and technology. He took up his studies there on November 2 1948, defended his thesis on April 28, 1953 and started his job there as an assistant as early as in 1951. As a part of his graduation work, he submitted a live action film (New Shift [Nová směna]), a documentary (Central Puppet Theatre [Ústřední loutkové divadlo]) and a very well received theoretical text called Film Camera (Filmová kamera). In 1952, he started to work as a cinematographer at the Czechoslovak Army Film company, where he remained until 1957. His first works include short promotional films (For a Joyful Life [Za život radostný], New Shift [Nová směna], Physical Education of Young Teachers [Telovýchova mladých učiteliek]). He also made a short documentary about the Theatre of E. F. Burian under the title of Army Artistic Theatre (Armádní umělecké divadlo) and the partly animated Central Puppet Theatre (Ústřední loutkové divadlo). In 1957, he was taken on by the Československý Film state production enterprise as a cinematographer for the Barrandov film studio. He remained at the post until the end of his life.

During his studies and after his graduation, he worked mainly with Vojtěch Jasný (their cooperation included It is Not Always Cloudy [Není stále zamračeno], Everything Ends Tonight [Dnes večer všechno skončí], September Nights [Zářijové noci], Desire [Touha], I Survived Certain Death [Přežil jsem svou smrt], The Pilgrimage to the Holy Virgin [Procesí k panence], When the Cat Comes [Až přijde kocour], All Good Countrymen [Všichni dobří rodáci] or Czech Rhapsody [Česká rapsodie], a film poem for the EXPO ‘70 in Osaka) and with Karel Kachyňa (Everything Ends Tonight [Dnes večer všechno skončí], The Lost Track [Ztracená stopa]). Later on, they renewed their cooperation with Little Mermaid (Malá mořská víla) and Death of a Fly (Smrt mouchy). In the 1960s, after participating in the team project Pearls at the Bottom (Perličky na dně), he started to work with filmmakers from the second generation of FAMU, known as the New Wave: Jaromil Jireš (The Cry [Křik]), Jan Němec (Diamonds of the Night [Démanty noci]), Ivan Passer (A Boring Afternoon [Fádní odpoledne]), Evald Schorm (Trojí přání, Psi a lidé [Dogs and People]) and with his wife Věra Chytilová (Daisies [Sedmikrásky], Fruit of Paradise [Ovoce stromů rajských jíme]. In 1968, he started to teach at the cinematography department of FAMU; he mainly focused on teaching color cinematography in general and color composition in particular. After being forced out of work for a while, he started to make films again in the early 1970s, most of them comedies. Several noteworthy films came out of his cooperation with Zdeněk Podskalský (A Night at Karlstein [Noc na Karlštejně], The Christening Party [Křtiny], What a Wedding, Uncle! [To byla svatba, strýčku!]) and with Oldřich Lipský (Straw Hat [Slaměný klobouk], Joachim, Put It in the Machine [Jáchyme, hoď ho do stroje], Solo for Elephant and Orchestra [Cirkus v cirkuse], Adele’s Dinner [Adéla ještě nevečeřela]). During that time, he also made short films, entertainment productions and TV recitals (Ploskovice Nocturno [Ploskovické nokturno], several episodes of the Rendezvous [Dostaveníčko] entertainment show, song recitals The Romance of the Rose [Román o růži] and Holiday [Prázdniny] and the Springs Covered in Snow [Zaváté studánky] clip programme).

In the 1960s, he also worked for the Laterna magika theatre; he worked on its alternative programme for tours along with Vladimír Novotný. However, the programme got censored and the cooperation broke up. He returned to Laterna magika in the 1980s not only as a cinematographer (Pragensia), but also a co-director (Black Monk [Černý mnich]) and co-writer (Odysseus). Starting from the 1970s and mainly during the 1980s, he also worked for foreign productions (especially German, but also British and American ones), including opera and book adaptations under director Petr Weigl (The Night of Lead [Die Nacht aus Blei], Maria Stuart, Mozart’s Journey to Prague [Mozartova cesta do Prahy], A Village Romeo and Juliet [Romeo a Julie na vsi], Dumky), TV series (Theodor Chindler, Wilder Westen, inclusive) or a short film based on Isaac Bashevise Singer’s Zlateh the Goat. In 1982, he made his only fully individual project, the Prague Castle (Pražský hrad) documentary, in which he was the cinematographer, writer and director.

This list is in itself a document of Kučera’s wide scope and of the diversity in his work. Jaroslav Kučera’s work is a mixture of realistic depiction on the one hand (seen both in his cinematography in the cinéma vérité style, and in his classical depiction, making the means of filmmaking invisible, the storytelling stronger and the audience’s identification with the fictional world greater), and of stylization on the other (inspired by various painting styles or related to the avantgarde radicality). On the one hand, he shows a raw, authentical, documentary-like image capturing day-to-day reality, or, on the other hand, he either highlights the idyll or deforms the picture with different amount of progressivity. On the one hand, there’s clarity, lucidity and accuracy of the image, on the other, there’s symbolicity, abstraction and geometry lacking clear contours or a link to reality. On the one hand, there are the seemingly arbitrary snapshots, on the other, the minutiously composed poses. On the one hand, ironing out all wrinkles in film image and in media practice to make it look seamless, on the other, a great amount of self-reflection and heightened visibility of the material substance. The dynamic countermovement also creates very specific states of motionlessness in the mid of motion pictures, a co-existence of halting and moving the image, balancing jerky, nervous movements with smooth, non-performative motion. In some of the films, these qualities are combined, mixed and shaded one into another, complicating further their classification.

Unlike other experimental cinematographers of his generation, he didn’t concentrate much on the depth of field or several plans in the image; he would rather work with figurations in a tableau-vivant-like style, with diagonals, verticals and horizontals, with the distribution of colours and the relations among them, and with lens speed. The surface is the main vanishing point, a tissue of relations that captures our sight and convinces us about the power of the image, its authenticity, elaborated easiness and persuasiveness; it is the projection of the new and the traditional, the original and the time-tested, the pathetic and the affective, the crumbling and the newly constructed, the vision and the narration; it is a proof that Kučera was able to make film image become a truly autonomous business.