“I think the sympathies which the film-truth attracted here, were based predominantly on other reasons than professional and critical. In a concrete historical situation, film-truth meant that the harsh reality of the current expression of people saying often very professedly what they really think, opened some windows to the creative workshop of documentary film equipped with embellished, well-lit pictures and blow-dried loquacious commentaries. The film-truth thus became a platform for a declaration of its author who, based on generalisation of some experiences, arrived at a conclusion.”[1]

After the reorganisation of the Krátký film studios in the 1950s, Studio of News and Documentary Film and Studio of Popular Science and Educational Film were established. Production focusing on popular science had a priority. The genre of socially analytical documentary stagnated until the beginning of the following decade which saw the establishment of Czechoslovak sociology and development of sociological research. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, an influx of new themes and personalities, mainly FAMU graduates, brough about a change.[2] The reason of the revival was the overall change of the cultural and political climate, introduction of new recording possibilities and trends prevalent in world cinematography (particularly cinema verité) which Rudolf Krejčík, the main subject of this article, mentions in the quote above.

Filmmakers such as Kurt Goldberger, Radúz Činčera, Bruno Šefranka, Evald Schorm, Václav Táborský, Jiří Papoušek and his brother František and Rudolf Krejčík strived for immediacy, truthfulness and authenticity of expression. At the same time, in opposition to schematisation and idea numbness of the existing documentary films, they promoted Grierson’s idea of “creative interpretation of facts.” They stopped simply reproducing the opinions of the portrayed side, they started expressing their own, often critical views on the given issues and, as Krejčík says, provided a look behind the scenes of documentary film.

New films were daring both politically and aesthetically. Significant contribution was provided by the Czechoslovak Army Film, which, led by several liberal dramaturges (e.g. Roman Hlaváč), moved away from purely military themes in the 1960s. Several documentarists spent their military service in the organisation. We will now take a closer look at one of them, Rudolf Krejčík.

Krejčík was born on 13th December 1934 in Prague. After finishing secondary school, he worked in a chemical factory for two years. In 1954, he began his studies at FAMU where he focused on documentary film dramaturgy. Already during his studies, he began working for the Studio of Popular Science Film. First as a driver and production assistant, then as a screenwriter and assistant director. After finishing film school and military service in the Army Film studio, he was employed as a director in Krátký film Praha. His first work was an instructional video about the bad habits of railway passengers Health on the Railway (Půl zdraví na kolejích, 1959).[3] Together with Radúz Činčera, they made a documentary titled Dancing Around Dance (Tanec kolem tance, 1960). In it, using archive footage and ironic commentary, which would become Krejčík’s favourite tools, they map the history of social dance. The film received an award at the Days of Short Film.

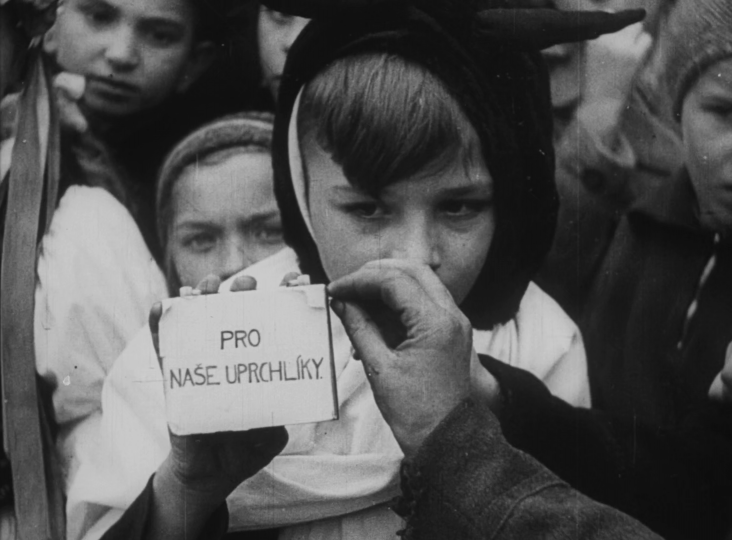

In his three following films, two of which he made during his military service in the Army Studio, Krejčík focused on Nazism, one of the main themes of his work. Fairy-Tale about a Castle, Children, and Justice (Pohádka o zámečku, dětech a spravedlnosti, 1961) is a caustic accusation of the former spokesperson of the Sudeten German Homeland Association Hans-Christoph Seebohm calling for justice despite his own dark past, and at the same time a defence of the expulsion of Sudeten Germans from Czechoslovakia and the nationalisation of their property. The commentary imitating the tone of fairy-tales was provided by actor Vlastimil Brodský whose voice the audiences knew from radio fairy-tales with gnome Hayaya. The film received an award from the Czechoslovak Army Film.

A strong resentment towards the Germans characterises also Krejčík’s medium-length documentary Fifth Column (Páta kolona, 1961). Krejčík used authentic never-before-seen archive footage to reveal the criminal past of former members of parliament for Henlein’s Sudeten German Party who continued to live as blameless and respected citizens of Germany after the war. They were even given important functions. However, the written records and archive footage Krejčík used prove these people were war criminals and ardent Nazis loyally serving Hitler. While exploring the possibilities of the documentary format, Krejčík continued with his most famous anti-Nazi film Every Day in the Great Reich (Všední dny velké říše, 1963) which won the Award of 20th Anniversary of the Liberation of Czechoslovakia.

Every Day used edited footage spanning from the beginnings of Nazism in Germany and Henleinism in Czechoslovakia to Hitler’s defeat. Compared to his previous two films, Krejčík doesn’t reveal any new facts. But he portrays Sudetenland from a different perspective than was customary. His film isn’t just a condemnation. Based on social and psychological foundations, it examines the lives and minds of people who decided the serve the Reich. What was the basis for their philosophy, psychology and morality? Krejčík tries to discover the essence of the historic reality through the subjective adjustment of citizens. Once again, he uses an ironic commentary and montage portraying a single theme in various contexts. His reflection on the genesis of inclination towards Nazism was the swansong of the Studio of the Popular Science Film. After another reorganisation of the Krátký film studio in 1964, individual studios were cancelled and replaced by dramaturgical-creative groups.

A Generation Without a Monument (Generace bez pomníku, 1964) oscillates between the then-popular survey and a testimony about the work of youth amateur theatre troupes. Footage from performances by troupes Kladivadlo from Kadaň, V Podloubí from Most and Kruh from Mariánské Lázně hint at problems young people had to deal with. Their casualness is in contrast with the hypocritical testimonies of adults who provide unequivocal answers to questions raised by young actors. They offer clear opinions on the young and culture and its un/necessity. Similarly harsh judgements, based on prejudice rather than direct contact with culture, the condition in which it originates, and people who create it, can be encountered here to this day.

Although the film was made in a rather loose social atmosphere, as evidenced by the provocative spirit of the theatre performances, Krejčík later recalled that the censorship committee requested many cuts: “There were several objectionable scenes, which were originally approved, but by the time we finished the film, the situation had changed. The committee raised objections to a song and a scene with a carousel which keeps on moving but the figurines stay still.”[4]

With Jan Špáta behind the camera, Krejčík made At the End of the Republic (Na konci republiky), a sequence for the anthology film Czechoslovakia 20 (ČSSR roku 20, 1965) chronicling the transformation of Eastern Slovakia.[5] The same duo was given an opportunity to go to Sweden where they made documentary A Sun Called Lucy (Slunce zvané Lucie, 1965) capturing the atmosphere of Christmas Stockholm.

Another work trip took Krejčík to Brazil. Working for Propagation Film, he made a short film about the dams on rivers Tiete and Paranaiba built in collaboration with Czechoslovak company Technoexport. During his seven-week-stay, he filmed footage which he later used to make two colour documentaries. Butantan (1966) was filmed in the Institute for Research of Natural Poisons which kept poisonous snake and used their venom to make antidotes. Mid-length film A Handful of Brasilian Pebbles (Hrst kamínků z Brazílie, 1966) shows Brazilian curiosities and tourist attractions in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo.

In 1966, Krejčík returned to the life of the German minority in Czechoslovakia. Film Staying with Neighbours (Cesta k sousedům, 1966) follows members of German intelligentsia who emigrated to Czechoslovakia before the war and published their own books and magazines banned in the Third Reich. Among the people who swore an oath to Czechoslovakia was e.g. Nobel Prize Laureate Thomas Mann. Once again, Krejčík went beyond simple stating of facts. He contrasts film footage, photographs and documents from Germany to testimonies and quotes from the work of scientists, writers and journalists. The film won an award at the IFF Oberhausen.

Krejčík won more domestic and international awards with his mid-length film The Law (Zákon, 1967), essay about the rules of human societies and his investigative documentary The Clues Lead to A-54 (Stopa vede k A-54, 1967) about the collaboration between the Czechoslovak intelligence and a member of NSDAP. At the end of the 1960s, just like his colleagues, he took advantage of the lifted travel restrictions. In August 1967, Krejčík and cinematographer Vladimír Skalský travelled to Canada where they – based on an agreement between Czechoslovak Film and the National Film Board of Canada – made a documentary film. Indian Summer (Indiánské léto, 1968) is framed with the celebrations of the 100th anniversary of the Canadian Confederation culminating at the EXPO 67 in Montreal. Krejčík, with the help of his editor Milada Sádková, used the recorded footage once more to make a short film about a meeting of hippies titled Love in (1968).

It was not until 1990 that Czechoslovak viewers had the opportunity to see a chronicle of seven days of the August 1968 Occupation of Czechoslovakia titled Seven Days to Remember. The film is a collective work by Rudolf Krejčík, Václav Táborský and other filmmakers filming in the streets during those fateful days. The footage was smuggled to Canada where Krejčík started editing it. But as he had to return to Czechoslovakia, the work was finished by Táborský. The emotional English commentary heard in the film was provided by Jiří Voskovec. Krejčík had another film which he was allowed to finish after the revolution – Searching for Home (Hledání domova) – following Czech citizens who emigrated to Germany after the events of August 1968.

In Denmark, Krejčík made documentary The Land of Queen Dagmar (Země královny Dagmar, 1969) and a year later in Africa, he was responsible for a series of films for UNSECO. The project titled Jambo Africa comprises titles Hic Sunt Leones, The Land of Queen of Sheba, Zebra versus Cow, Under the Snows of Kilimanjaro, Too Many Elephants? and The Last Bushmen on Kalahari. In addition to this series, Krejčík also made a film about the Malindi Marine National Park in East Africa Safari on Sea (Safari na vodě, 1972).

During the normalisation era in Czechoslovakia, Krejčík focused more on commissioned work rather than his own which would openly and critically analyse reality. He made a portrait of Czech orientalist Bedřich Hrozný tiled Bird Tracks on Wet Sand (Ptačí stopy na mokrém písku, 1979) and film medallions of Vienna and Warsaw. He repeatedly filmed the Spartakiade, in films The Beauty of Movement (O kráse pohybu, 1975), Czechoslovak Spartakiade 1975 (Československá spartakiáda, 1975) and Czechoslovak Spartakiade 1980 (Československá spartakiáda 1980). Another big sporting event, a ski race, is covered in The Jizera 50 (Jizerská padesátka, 1976).

Also in his later documentaries, Krejčík tried to resourcefully use archive footage. At least this way, without his typical sarcastic commentary, he was able to imprint his trademark to the film. Through his work and thinking, Krejčík inspired further generations of filmmakers as a lecturer on FAMU. One of his students was for instance Helena Třeštíková.

Rudolf Krejčík died in 2014. In 2001, he donated part of his written archives to the National Film Archive. They included his contract with FAMU, correspondence and scripts and other materials related to popular science and commissioned films he made for Krátký film.

Notes:

[1] From Rudolf Krejčík’s talk in the panel during the 6th Days of Short Film in Karlova Vary. Senta Wollnerová, Víme, při čem jsme? Divadelní a filmové noviny 8, 1965, no. 19, (14th April) p. 3.

[2] Independent Department of Documentary Film was established in 1961, until then, documentary film was taught at the Dept. of Direction

[3] Among other Krejčík’s early educational films were titles such as A Common Disease (Taková obyčejná nemoc) about flu viruses, It’s Not Karel’s Fault (Karel za to nemůže), a humorous criticism of the flaws of construction industry and popular science film Science in our Backyard (Věda za našimi humny).

[4] Rudolf Krejčík, Nekrolog za mého cenzora. Filmové a televizní noviny, 1968, no. 7, p. 4.

[5] Krejčík returned to Eastern Slovakia in 1968 to film Local Radio (Místní rozhlas) about introducing radio broadcast in the village of Ruský potok in the Humenná district.