Grotesque horrors, parodies of classic horrors, animated horrors, psychological horrors, puppet horrors, attempts at lyrical horrors, paper parodies of horror, romantic detective horrors – is it really so hard to find a pure and simple horror film in the history of Czech cinema?

“Asides from beauty and miracles, life also offers the presence of fear and horror. Fear of death. Death itself, and horror derived from, the darkness and emptiness. It is all very fascinating.”[1]

We have previously examined Czech filmic efforts across genres including singing, dancing and drama (musicals), and also those which are characterised by fantastical stories and archetypal characters (fairytales). This time, we examine a genre, which as a rule is characterised by its ability to evoke a cognitive reaction from viewers – horror. As can be read in the publication Film a filmová technika (Film and Film Technology), the emotions which are evoked as viewers watch a horror film have a biological foundation and are in essence rooted in a fear of death, usually the result of an encounter with a dangerous and inhuman creature or a horrible monster.[2]

The unflagging popularity of horror films serve as a testament to the paradoxes inherent in this genre – for asides from fear and disgust, as a rule viewers can also experience delight from the opportunity of a “safe” encounter with fictional representations of manifestations which evoke such terror in us. And so horrors can serve as a kind of useful training ground to prepare us for the dangers of the real world, from which artists have been deriving inspiration for centuries.

“A representation of fear, foreboding, and terror – all that we currently ascribe to the notion of ‘horror’ (sometimes itself found within the sci-fi genre) has a certain tradition. If we set aside works that were viewed as trashy even when they were first published, then we find that the list is actually not that long. First we had E. T. A. Hoffmann (1776–1822), arguably the founder of the genre in both European and world literature. Perhaps that also concurrently served as the creation of the psychological genre. After that came his contemporaries Edgar Allan Poe (1809–49) and Nikolai Gogol (1809–52), and only in their wake the embittered Ambrose Bierce (1842–1914?).”[3]

Similarly as with other genres, film horrors also have literary roots. Gothic horrors predominantly derive from 18th and 19th century Anglo-American authors such as Bram Stoker,[4] Robert Louis Stevenson, Mary Shelley, Howard Phillips Lovecraft, the aforementioned Ambrose Bierce and others. Their frightening tales were themselves inspired by ancient myths and legends as well as from the era of Romanticism, which emphasised intuition and emotion over the rationalism of the Enlightenment. During the 19th century, the proliferation of the tabloid presses contributed to increased public interest in real-life crime stories. This then served as an opportunity for horror fiction writers such as Edgar Allan Poe, who shifted the genre from the supernatural to the psychological.

A no less significant inspiration for film horror is found on the theatre stage. One notable outlet was the Paris-based Grand Guignol theatre, opened in 1897 with a single goal – to shock audiences with violent and naturalistic horror shows. At around the same time Georges Méliès stunned early film audiences with “the first horror movie” Le manoir du diable (The House of the Devil, 1896) featuring scenes of a bat transforming into a devil. Meanwhile, Louis Lumière depicted a dancing skeleton in the short effects film Le squelette joyeux (The Dancing Skeleton, 1897). And with that, the first chapter of film horror was written.

Czech horror undoubtedly owes a great deal to writers such as Karel Hynek Mácha, Jakub Arbes, Ladislav Fuks, Josef Škvorecký and Jan Zábrana. Yet the genre never took off in the country the way it did in the United States, United Kingdom, Italy, Spain, or (in particular in recent years) France. Terrifying films, in which the central characters face unnatural beings and forces which defy rational explanation, were never popular enough in this country to build up to a tradition which could then be further cultivated and developed.

The casualties of this dismissive attitude towards genre films by Czech artists were not merely limited to horror. Indeed, the very concept of a genre, with a certain set of rules, has long been viewed by Czech filmmakers and viewers as a restricting factor which limits the potential end product. In recent years, even projects supported by the Státní fond kinematografie (State Cinematography Fund) demonstrate this line of thinking. But the reasons for this widespread dismissal of genre elements may not be purely creative, but also connected to the higher costs associated with such projects, as evidenced by last year’s published findings by the Fund’s board:

“Applications also included genre films, (the thriller Oranžový pokoj [Orange Room], Gangsterka [Female Gangster], the fairytale Čertí brko aka Horkou jehlou [The Devil’s Quill, aka Hot Needle]) and all found themselves relatively high up the list; however, given the available financial resources, none were ultimately supported.”[5]

Repulsive imagery

At the start of the 20th century, the Czech lands also bore witness to a debate over the potential negative impact of films on the morals of children and young people. Darkened movie theatres, which were musty “with poorly ventilated beer and sweat”[6] were blamed by some for a rise in amoral behaviour, criminality and alcoholism. During the time of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the critical voices of self-declared defenders of public morality brought about a number of movements pushing for cinema output to be reformed. Emotive discussions regarding the “moral filth” which was “titillating viewers”[7] contributed towards greater levels of caution regarding the impact of violent or sexual films on more sensitive viewers, leading to tighter oversight by censors, which was carried out by local censorship officials located in Brno, Prague and Opava. But even despite these tougher controls over the nascent film industry by the Austro-Hungarian authorities a number of genre films were still produced – including the horror-themed slapstick comedy Noční děs (Night Terror, 1914), in which a number of characters try to get rid of the body of a supposedly dead person.

The boom in filmic monsters during this era is said to have its roots in the experience of the First World War, which for the first time presented the public with an experience of mass death and mutilation. At the same time, we can look for the roots of expressionist horrors such as The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) in the psychological and financial instability of post-war Germany. A number of years later, the same kind of financial uncertainty inspired a legendary slew of horror films from US studio Universal (Dracula, 1931; Frankenstein, 1931; The Mummy, 1932).

Assessing the genre choices of Czechoslovak filmmakers, one could conclude that the country never experienced any such economic or other crises. Comedies and films inspired by escapist “Červená knihovna” (mass-market novels) tended to run away from reality rather than offering allegorical commentaries. Film viewers, too, wanted movies to offer pleasant distraction and escape, to present glamorous well-known stars, and to showcase popular trends. Viewers need not have been concerned that such films would confront them with an unsettling reality. Despite the fact that 1920s-30s Czechoslovak cinema was not entirely without thoughtful, and even political, content, the First Republic era was clearly characterised by the popularity of escapist entertainment. An avoidance of painful aspects of reality, and an unwillingness to translate political, economic and social questions into filmic genre stories is something which, in fact, continues as a trait of Czech cinema to this day.

The mystery-drama Příchozí z temnot (The Arrival from the Darkness, 1921) serves as one of the aesthetic manifestations of German expressionism. Directed by Czech writer, director and actor Jan Stanislav Kolár, the film was shot at a number of Czech castle locations (Karlštejn, Okoř, Český Šternberk) and also at the German Atelier am Zoo studios in Berlin. The story for the star-studded film (featuring Karel Lamač, Anny Ondráková, and Theodor Pištěk), which contains gothic horror elements, was written by Karel Hloucha, author of a number of fantastical novels. The commercially successful and cosmopolitan project enthralled not only Czech viewers with its ambitious mixing of the present-day and the Prague of Rudolf II. The plot tells the story of a 16th century aristocrat, who drinks a potion, wakes in the 20th century, and encounters a woman who resembles his deceased wife.

The reputation of horror as a less-than-respectable genre which could have a negative impact on young people (and consequently reduce the overall popularity of cinema) continued throughout the entire life of the First Republic, in spite of the international success of Příchozí z temnot. Even though folk comedies and sentimental melodramas steered clear of the supernatural, they nonetheless fulfilled a social function of providing a reliable staple of escapist entertainment, without offending moral crusaders or endangering the livelihoods of film producers.

The output of the post-Second World War nationalised Czechoslovak film industry was officially supposed to foment independent thinking and socialist-style patriotism, and promote the country and national interests both at home and abroad in the newly liberated country. Naturally, under such a concept, it proved highly difficult to bring to fruition “pictures of the repugnant kind portraying the decaying of life; terrifying, bloody and inhuman stories”.[8] Film output was strongly determined by the socio-historical context and political climate of the time. However, one way it did prove possible to add horror elements to contemporary feature films was to adapt a classic literary horror story.

Podobizna (The Portrait, 1947) was inspired by an eponymous short story from author Nikolai Vasilievich Gogol’s Arabesques collection. The film tells the story of a painting, which brings misfortune to those in its proximity. The chilling atmosphere is aided by a strong interplay of light and shadow courtesy of cinematographer Jan Roth, and also a production design inspired by contemporary painter Josef Liesler. A contemporary reviewer praised the aesthetic aspects of the production:

“The painter’s oscillation between artistic prostitution and heartfelt, truthful art is one of the most fateful questions for an artist. (Director) Slavíček has overwhelmingly succeeded in tackling this very question, both in an optical sense and also frequently in the dramatic sense, too, offering direction which exceeds the quality of the script.”[9]

After the communist putsch of February 1948, the pressures grew significantly on films to conform to the official party line, and to be used to educate, regiment and indoctrinate the populace. Today, strongly ideological “building a better future” dramas such as Botostroj (Giant Shoe-Factory, 1954) and Nástup (The Start, 1952) tend to evoke greater levels of disgust than a number of famous American horrors made at the same time, such as Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954) or The Thing (1951). Simply put, unlike in the United States, horror films were definitely not the order of the day for 1950s Czechoslovakia.

One key difference between Eastern Bloc and Western films of this time is that Western films presented metaphorical genre allegories, while Eastern Bloc films presented a less-than-subtle direct line of indoctrination. And so a sci-fi horror film such as Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), which has been interpreted as an expression of a fear of the “Red Menace”, remains a classic. While a film such as the blunt anti-American propaganda drama Únos (Kidnapped, 1952) now only elicits either disgust or laughter.

Grotesque grimacing horror

The liberal political and cultural climate of 1960 Czechoslovakia led to a boom in genre films.

“The era from 1960 onwards is characterised by a broadening of the palette of genre films which found success with audiences (science fiction, animated feature-films, sexual awakening films, horror) as well as a concurrent decrease in interest in other genres (dramas).”[10]

It wasn’t just Podobizna that took inspiration from existing prestigious literary works. Another example is the psychological horror Spalovač mrtvol (The Cremator, 1968) from director Juraj Herz. However, similarly to the film, the author of the book Ladislav Fuks did not remain very long as a darling of the establishment – shortly after its premiere Spalovač mrtvol was withdrawn from distribution and placed by the authorities in a “vault” of banned films.[11] Irrespective of the views of normalisation-era ideologues, Fuks, who belonged to a generation which had vivid memories of Nazi concentration camps, remained one of the maestros of Holocaust-themed and horror-tinged psychological prose. Juraj Herz also had personal childhood experiences of the horrors of the Second World War.[12] The budding director and the established author spent two years together writing the film’s script[13]. Cinematographer Stanislav Milota also played a key role in crafting the finished film, another factor which helps to explain why both the literary and filmic versions of Spalovač mrtvol are organically so similar.

As a disturbing study, detached from rational thought, today Spalovač mrtvol is considered not only one of the most disturbing, but also one of the best examples of Czechoslovak cinema. Other reasons for the effectiveness of the film include that it was shot in real-life crematoria (which remained partially operational even as cameras rolled); also effective is the music of Zdeňek Liška and actor Rudolf Hrušinský’s absorbing performance in the central role as crematorium employee Karel Kopfrkingl. In spite of the sheer number of brutal murders which take place in the film, as a horror Spalovač mrtvol retains a genre “impurity” characteristic of Czechoslovak cinema. While watching the film, viewers often react to the morbid humour with a mix “of laughter and nausea.”[14], and its “satirical content gradually solidifies into a grotesque mixed-up horror.”[15]

For Herz, it was an appeal to the exploration of new comedic boundaries that helped him gain support for Spalovač mrtvol with the heads of the state-run film industry. Yet at the time of its release in the spring of 1969, the post-invasion climate in the country gave viewers very little to laugh about. Spalovač mrtvol did not become a cult film until after November 1989. The fact that this film – the first strict Czechoslovak horror – was made at all might lead to the conclusion that the intellectual elites had at last embraced this long-neglected genre. However, the genre implications of Herz’s third feature-film are perhaps better understood by placing it in the context of its times:

“And so we have our first domestic grotesque horror, but it is a Czech-style horror, by which I mean to say that it is on the intellectual level of the very best works of our cinema of recent years; it is thoughtful and the terror it presents is combined with irony, and the deeds it presents possess a wider symbolic meaning in the larger scheme of things.”[16]

Similarly to Spalovač mrtvol the television film Meze Waltera Hortona (The Limits of Walter Horton, 1968), based on a story by John Seymour Sharnik, also evoked a curious mix of fear and laughter in audiences. This time, Rudolf Hrušínský portrays music manager Vladimír Brodský, who one morning discovers out of the blue his amazing talent for playing the piano. But in this case, the horror ingredients in this film are so slight that they may even go unnoticed by modern audiences.

More than twenty years after Podobizna, the horror potential of enigmatic Old Prague was mined by a trio of directors – Miloš Makovec, Jiří Brdečka and Evald Schorm – in the now largely forgotten anthology film Pražské noci (Prague Nights, 1968). The first of the three morbid tales is set in the Gothic era, the second during the Renaissance, and the third presents a Rococo-themed stylisation. However, unlike with Spalovač mrtvol audiences failed to embrace Pražské noci, either during its release during the misfortune-filled year of 1969, or in subsequent years. And yet contemporary-era viewer feedback demonstrates that the Czech appetite for horror had by no means abated:

“(…) certain genres have been and continue to be sidelined on the screens of our cinemas (westerns, horrors), but it is precisely these that would help to fill the tills of cinemas, while artistic expression need not necessarily be reduced to a minimum.”[17]

The last echoes of the experimental free-thinking climate of the 1960s New Wave is found in Valerie a týden divů (Valerie and Her Week of Wonders, 1970), a stylised horror fairytale about the sexual awakening of an adolescent girl. Inspired by an eponymous gothic novel by Vítězslav Nezval, the film, too, presents a poetic, absurd and bizarre dreamscape of surreal imagery. Valerie a týden divů is set in a world between dreams and reality, and mainly won acclaim with foreign audiences. Unlike normalisation-era critics, viewers in the West lauded the film’s aesthetic elements – the very kind which were rendered taboo for the next twenty years in Czechoslovakia. These included a heavily stylised mise-en-scène (courtesy of Ester Krumbachová), absorbing poetical surrealism, an indeterminate representation of time and space, significant eroticism, complex symbolism, and a need by viewers to ponder deeper meanings.[18]

Anti-normality

Beyond the borders of Czechoslovakia, however, horror films were experiencing a boom during the 1970s. With graphic news reports about the Vietnam War beamed into citizens’ homes, audiences became far more able to stomach seeing gory imagery on the big screen. Consequently, filmmakers had to stretch the boundaries. Horrors such as The Last House on the Left (1972), The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) and Dawn of the Dead (1978) reflect the raw aesthetic of contemporary news and documentary reports. Such films ripped viewers from their zones of comfort, and offered up not just explicit gore but also a subversive criticism of consumer society.

Conversely, the communist regime sought to keep the populace saturated on all fronts so as to maintain a sense of apathy towards the political situation in the country. And so, if film critic Robin Wood’s characterisation that horror is based around the idea of normality being disrupted by the cruel entrance of a monster is true, one can further posit that in a fully normalised Czechoslovakia the very existence of a genre which sought to disrupt the status quo would be entirely unacceptable to the regime.[19]

Those who grew up during this period in Czechoslovakia will certainly remember that the most terrifying normalisation-era films were all of the animated variety. Old canastoria (“story singer”) provided the inspiration for Jsouc na řece mlynář jeden (There Was Once a Miller on the River, 1971) a ballad-like story about a soldier killed by his own parents, and a joint artistic effort by director Jiří Brdečka and designer Eva Švankmajerová. Meanwhile, a Lusatian-Sorbian legend about the sorcerer Krabat was the subject of Čarodějův učeň (The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, 1977), the penultimate film by Karel Zeman. In 1978, author Karel Erben’s Svatební košile (Spectre’s Bride) was transformed by director Josef Kábrt into an eponymous animated horror.[20] And Krysař (The Pied Piper, 1985), from director Jiří Barta, remains one of the most chilling adaptations of the medieval legend.

As far as fomenting shock and fear in young audiences, animator and filmmaker Jan Švankmajer is a category unto himself.

The author of disturbing films such as Kostnice (The Ossuary, 1970), Kyvadlo, jáma a naděje (The Pendulum, the Pit and Hope, 1983) and Něco z Alenky (Alice, 1988), to this day Švankmajer, along with Juraj Herz (albeit a Slovak native), remains the only domestic director to consistently make films designed to shock and confront audiences via fantastical imagery mined from deep within the human sub-conscious.

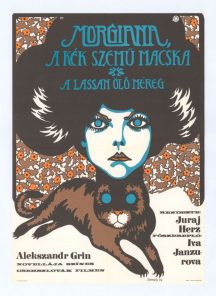

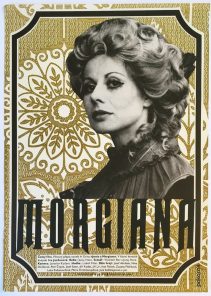

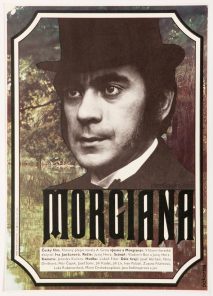

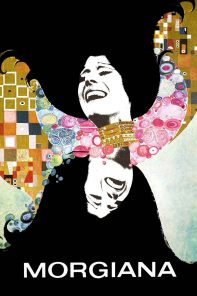

During the 1970s, Herz’s unwillingness to submit to the aesthetic norms of his era, coupled with his fascination with the darker sides of human existence, are best illustrated by a number of decadent fairytales, which provoked the management of Barrandov Studios with their sadomasochistic motifs and high levels of visual stylisation. For obvious reasons, Morgiana (1972), Panna a netvor (Beauty and the Beast, 1978) and Deváté srdce (The Ninth Heart, 1978) have never been fodder for Christmastime television seasonal entertainment. And rather than as serving as an example of quality Czechoslovak children’s programming, today such films serve far better as examples of the subversive application of horror elements in one of the few genres permitted by the former regime into which such elements could naturally fit.

Upír z Feratu (Vampire of Ferato, 1982) holds the reputation as the most “mutilated” Herz film, and was unable to escape the intervention of the censors. The film is a balance between the grotesque and shocking and is based on a Josef Nesvadba short story called Upír po dvaceti letech (Vampire After Twenty Years). The story, about a racing car fuelled by the blood of its drivers, had certain gory and erotic scenes deleted in the scripting stage. Herz then had to cut other scenes out of the completed film. Partly as a result of such interventions, this film about a hybrid-fuelled car is itself something of a genre hybrid, combining elements of the vampire horror, detective story, shocking thriller, and parody.[21] Thus, viewers seeking a Czechoslovak horror film which would show more than it concealed would have to look westwards.

“It is worth considering why younger viewers are expressing a greater interest in certain forms of genre entertainment (for example such classic youth favourite genres as westerns and horror films).”[22]

Foreign films helped somewhat to satiate the appetites of young Czech viewers for horror – and it was in this regard that the term “horror” was most used by the contemporary press. However, this was often bandied about quite loosely. The description of Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979) as a “cosmic horror” is less open to dispute. However, labelling Truffaut’s noir homage film La mariée était en noir (The Bride Wore Black, 1968), the crime thriller The Boston Strangler (1968) or the disaster movie The Towering Inferno (1974) as horrors is arguably a stretch too far. Meanwhile, The Fly (1986) was contemptuously dismissed as an “awful and unmatchable horror (…) featuring expert levels of realism.”[23] Uncertainty over what exactly defined a horror, coupled with doubts over the aesthetic value of some of its most celebrated titles, affirm an insufficient familiarity in Czechoslovakia with the horror genre, resulting in clumsy attempts to even properly describe its core components.

Young intellectuals

The modern “horror” label only began to be widely used by Czechoslovak film periodicals during the 1990s in conjunction with an inflow of US titles such as A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984). The presentation of this film within the pages of Kino magazine in January 1991 begins with a previously unthinkable suggestion: “Imagine dreaming about some guy who is cutting you up with a razor, and then you wake up and see the sheets are covered with blood.” Add to that the following subsequent definition of what represented a quality genre film: “A good horror will shake you to your core, while at the same time you feel relatively safe.”[24] Asides from film critics, the various shades of the horror genre were also described by Czech directors open to foreign influences:

“Naturally, to go in 1972 to Barrandov and propose an idea of that nature would be nonsense, because horror was among the forbidden genres. I was only able to return to the passion of my youth after late 1989, when the restrictions began to be lifted,”[25] noted director Jaroslav Soukup in a contemporary interview. The artist with an affinity for American cinema was specifically referring to his Svatba upírů (The Vampire Wedding, 1993), which, thanks to censorship and difficulties raising funds (the budget allegedly came to USD 820,000, including marketing costs) could only be made after the Velvet Revolution and after the completion of 1991 and 1992 sequels to the hit films Discopříběh (Disco Story, 1987) and Kamarád do deště (Rainy Day Friend, 1988).

But once again, what emerged was not a pure horror film, but rather an exaggerated mix of genres, which affirmed the essential humour of the Czech nation. Since the beginning of cinema, Czech filmmakers have used humour to excuse the impossibility (or their inability) to create a fully-fledged genre story.[26] And so if Czechs cannot compete with overseas examples, then they can at least subvert them.

“It was probably a kind of crime and horror film in one. Because the situations depicted are so stark, humour is the best option during times of dread. That is a beautiful combination.”[27]

Šimon and Michal Caban described their quirky tribute film marking the 200th anniversary of the death of Mozart as an “expressive musical and moralistic cultural horror”. Such a classification reflects that even Don Gio (1992) is not a pure horror, but also an ironic play with certain rules of the genre. No less a distinctive horror interpretation is found in Krvavý román (Horror Story, 1993) based on author Josef Váchal’s literary reflection on 19th century paraliterature. For director Jaroslav Brabec Krvavý román served as a filmic equivalent of the literary parody, which mocks the clichés of second-rate literature; stylised as a silent film, the exaggerated atmosphere seeks to evoke a number of bygone historical eras. However, this domestic horror, which can be described as the most striking example of Czech attempts at matching the styles of foreign horrors (specifically German expressionist ones) is, in fact, more of a faux horror, emphasising lampooning over any genuine shocks.

Co-directors Marek Dobeš and Štěpán Kopřiva brought a typically detached Czech interpretation of horror with their cult horror parody Byl jsem mladistvým intelektuálem (I Was a Teenage Intellectual, 1998). In the film, the main characters are not threatened by vampires, zombies or werewolves, but rather by long-haired intellectual young men, who, before biting their victims, read them some quotes from German philosopher Hegel. The same two filmmakers once again focused on young intellectuals – this time B-movie film buffs – in their zombie comedy Choking Hazard (2004), which includes kung-fu and splatter slapstick, a device also used in the early films of Peter Jackson.

It is mainly Czech horror fans like Dobeš, Kopřiva and also Roman Vojkůvka – Někdo tam dole mě má rád, (Someone Down There Likes Me, 2008) and Total Detox (2011) – often recruited from the ranks of student filmmaking, that are responsible for more Czech horror being produced in the last 25 years than during the previous total 100-year history of Czechoslovak film. One only need visit the Czech-Slovak Film Database (ČSFD.cz) and search for student and amateur horror films to find such striking titles as Rozvod mrtvých (Divorce of the Dead, 2011), Vajgložrout: legenda kyberny (Butt-eater: The Legend of Cyber, 2011) or To není moje sestra! (That’s Not My Sister!, 2015).

Of the dozens of student and amateur more-or-less Czech horror films, the Christmas slasher Bloody Merry Christmas (2007) was able to rise above the crowd. Meanwhile, the animated horrors Duchové lesa (Spirits of the Forest, 2013) and Třída smrti (Class of Death, 2013) impressed critics with their artistry. Among its many listed genres including fantasy and fairytale, student film Lesapán (Leshy, 2015), inspired by the stories of Božena Němcová and Karel Jaromír Erben, also contains horror elements. Meanwhile, the professional – albeit low-budget – production of Juraj Jerz’s T.M.A. (2009) represents one of the purest Czech genre horrors of recent times. The same can be said of Nenasytná Tiffany (Greedy Tiffany, 2015), a horror comedy about human avarice, which critics described as one of the most original Czech films of the year.

Fans of the genre also enjoyed Ghoul (2015), a domestic response to the wave of “found footage” horrors, filmed via a hidden camera style by director Petr Jákl in the Czech Republic, Ukraine and the United States, where prior to its DVD release, the film was afforded a limited theatrical run. The ability of Ghoul to compete domestically with foreign blockbusters such as American Sniper (2014) and Fifty Shades of Grey (2015) demonstrates that the Czech public has an appetite for quality home-made genre films. The problem, albeit, remains with the abilities of Czech filmmakers to produce such movies, and thus bring back the horror genre from the peripheries of Czech cinema.

Horrors such as Poslední výkřik (A Killer in Prague, 2012), Isabel (2013) and Svatý Mikuláš (St. Nicolas, 2014) can be viewed as an alternative to B-movie-style horror trash. Curiosity seekers may be attracted to the fact that film critic František Fuka awarded zero percent to the first two of these movies on his blog, which usually means “so awful as to be entertaining”. According to Fuka, Poslední výkřik “makes a mockery of all fans of horror and victims of the Holocaust.”[28] Meanwhile, asides from a series of unintentionally comic scenes, the first purely Ostrava-based horror Isabel offers a fork-yielding vampire queen[29], while the narrative inadequacies of the best rated of the three, namely Svatý Mikuláš, were summed up by critic Mirka Spáčilová thus: “Although the lead characters perform with a pleasant authenticity, before they have all gotten to know each other, helped each other, packed, joked, gotten drunk, and then finally headed out to make a fateful reportage on one murky morning, the rules of drama dictate that at least half of them should have somehow been covered in blood or fallen as martyrs by that point.”[30]

What is clear is that in the aforementioned examples, the desire to make a horror was greater than the technical or storytelling skills of the filmmakers. The abundance of failed and unwittingly humorous Czech horrors is in turn increasing the reluctance of Czech audiences to risk going to the cinema to see such films. Furthermore, the term “Czech horror” hardly evokes a set of specific expectations. And so, aside from a core of die-hard horror fans, audiences are confused as to what to expect, because they have yet to see sufficient quality genre films to enable a viable classification. In fact, in all likelihood, they would not have even seen a single good example.

In his book The Philosophy of Horror: Or, Paradoxes of the Heart, American art philosopher Noël Carroll offers a well-argued definition of horror. In the case of horror, Carroll states, what is key is the emotional reaction of characters to a monstrosity, in which repulsion is connected to a sense of peril. The fear and disgust experienced by the films’ characters then help to evoke similar emotions in viewers – ideally this relationship should represent a direct mirror.[31] Despite the fact that Carroll only analyses the motives and strategies associated with one kind of horror film, his critique is nonetheless helpful in understanding why Czech horror films frequently evoke unintentional emotional reactions – meaning laughter. This serves as a testament to the peculiar approach of Czech filmmakers to this genre, as well as an overall inability to film a horror which genuinely evokes fear rather than being deliberately or unintentionally humorous.

Our brief foray into the history of Czech horror films ultimately indicates that although a handful of horror films have emerged in the country, we should in fact be glad that audiences have not had to sift through even more such poor-quality output. However, we should also not give up hope that perhaps soon – say with the release of Polednice (The Noonday Witch, 2016) – a Czech horror film will ultimately emerge to match the quality of the iconic classic Spalovači mrtvol.

Martin Šrajer

Notes:

[1] Ladislav Fuks interview with Václav Tikovský for the magazine Československý voják. Quotes via Jan Poláček, “The Story of Spalovače mrtvol, a Double Portrait of Ladislav Fuks”. Prague: Plus 2013, p. 39.

[2] Otto Levinský, Antonín Stránský and co., Film a filmová technika. Prague: Státní nakladatelství technické literatury 1974, p. 115.

[3] František Bráblík, Likely sources for Spalovač mrtvol. Filmový sborník historický 4. “Czech and Slovak Cinema of the 1960s”. Prague: National Film Archive 1993, p. 131.

[4] “Stoker’s Dracula Now Has a Czech Adaptation”; in 1979, Anna Procházková directed the TV film Count Dracula.

[5] Committee deliberation results – production of feature-films, complete development of animated films. fondkinematografie.cz: http://www.fondkinematografie.cz/vysledky-rozhodovani-rady-vyroba-celovecerniho-filmu,-kompletni-vyvoj-animovaneho-filmu.html

[6] A cautionary article by one angry Prague teacher, printed February 24, 1910 in Národní listy. Dejmek, Petr, “Haunted Children”. Cinepur 2003, no. 26, p. 21.

[7] Both quotes viz Petr Dejmek, c. d.

[8] Defining the horror genre by Miloš Fiala in a review of Spalovač mrtvol. Miloš Fiala, Spalovač mrtvol. Rudé právo 1969, 20.03., p. 5.

[9] -žlm-, Critical notebook: Portrait. Filmová okénka 1, 1948, no. 1 (31. 1.), p. 2.

[10] Jozef Majchrák, On the issue of audience viewing habits and the plans to battle for viewers. Panoráma: A Collection of Film Theory Essays 1978, no. 1, p. 29.

[11] If the issue is a re-evaluation of the official stance towards Fuks and his works, then a belittling Rudé právo text entitled “A Notably Muddy ‘Modernity’” from Fedor Soldan, an editor of a collection of poems on Lenin, is telling. Viz Fedor Soldan, “A Notably Muddy ‘Modernity’ – the Undeserved Fame of Ladislav Fuks”. Rudé právo 1970, 4. 9., p. 5.

[12] Viz for example: “I was certainly influenced by my concentration camp experience; I was ten years-old when they sent me there.” Alena Plavcová, “A Damned Black Riding Hood – An Interview with the King of Czech Horror”. Lidovky.cz: http://www.lidovky.cz/zatracene-cerna-karkulka-rozhovor-s-kralem-ceskeho-hororu-pnh-/kultura.aspx?c=A100704_125521_ln_kultura_tsh

[13] Although the book was published a mere year before the premiere of the film, accounts suggest Herz had the opportunity to read Fuks’ manuscript beforehand. Viz Jan Poláček, c. d., p. 162.

[14] Peter Hames, The Czechoslovak New Wave. Prague: KMa 2008, p. 249.

[15] Jan Žalman, Silenced Film. Prague: KMa 2008, p. 258.

[16] Miloš Fiala, c. d.

[17] Letter from reader D. Bully, “Letters”. Filmové a televizní noviny 2, 1968, no. 18 (18. 9.), p. 6.

[18] Rudé právo’s Jan Kliment, head of the paper’s cultural section, dismissed most of the aspects of the film. Jan Kliment, “Surprise at Valerie”. Rudé právo 51, 1970, no. 258, p. 5.

[19] Robin Wood, An Introduction to the American Horror Film. In Bill Nichols (ed.), Movies and Methods. Berkeley: University of California Press 1985, p. 195–220.

[20] Colourful film illustrations for a large part of Kytice were presented to audiences in 2000 by F. A. Brabec, whose output wowed some and appalled others with his adaptations of Erben’s works. Critics argued he had failed to evoke the ballad-like atmosphere of the literary works.

[21] A comparable hybrid example is the mysterious parable Vlčí bouda (Wolf’s Hole, 1986), in which, with great verve, Věra Chytilová merged the elements of sci-fi, horror and social satire.

[22] Jozef Majchrák, “Notes on the Subject of the Entertainment and Artistic Functions of Films”. Panoráma: A Collection of Film Theory Essays 1980, no. 4, p. 27.

[23] Štefan Vraštiak, “Fest 87”, Zpravodaj československého filmu 13, 1987, no. 5, p. 33.

[24] “Terror in Jilmová Street”. Kino 46, 1991, no. 1 (25. 1.), p. 14.

[25] Iva Hlaváčková, Jaroslav Soukup: “Marriage of Vampires: A Film that was Almost Never Made” Kinorevue 3, 1993, no. 20 (20. 9.), p. 18.

[26] Recall “Czech-style westerns” such as Limonádový Joe aneb Koňská opera (Lemonade Joe or Horse Opera, 1964) or for a long time the only Czech comic-style film Kdo chce zabít Jessii? (Who Wants to Kill Jessie?, 1966).

[27] Miroslav Horníček in an interview with Kinoautomat. -sb-, “Delayed Success”. Filmové a televizní noviny 1, 1967, no. 13 (28. 12.), p. 3.

[28] František Fuka, “Last Cry”. FFFILM: http://www.fffilm.name/2012/08/recenze-posledni-vykrik-0.html

[29] František Fuka, Isabel. FFFILM: http://www.fffilm.name/search?q=Isabel

[30] Mirka Spáčilová, “Again Horror, Again Domestic, and Again Hunting Demons”. idnes. cz: http://kultura.zpravy.idnes.cz/recenze-film-svaty-mikulas-ddm-/filmvideo.aspx?c=A150305_163031_filmvideo_vha

[31] Noël Carroll, The Philosophy of Horror: Or, Paradoxes of the Heart. New York: Routledge 1990.