‘Take Šváb! How come he does nothing? He isn’t stupid. Despite everything, I can’t say that […] It could be that he’s lazy. OK. But just look at this: he plays with musicians. Once or twice a week. At least. He has his silent film, and so, again, he goes twice a week to the archive. He visits the ballet. When the speedway’s on, he can’t miss it. Not to mention the fact that he also goes to work. So is this a lazy person?!’[1]

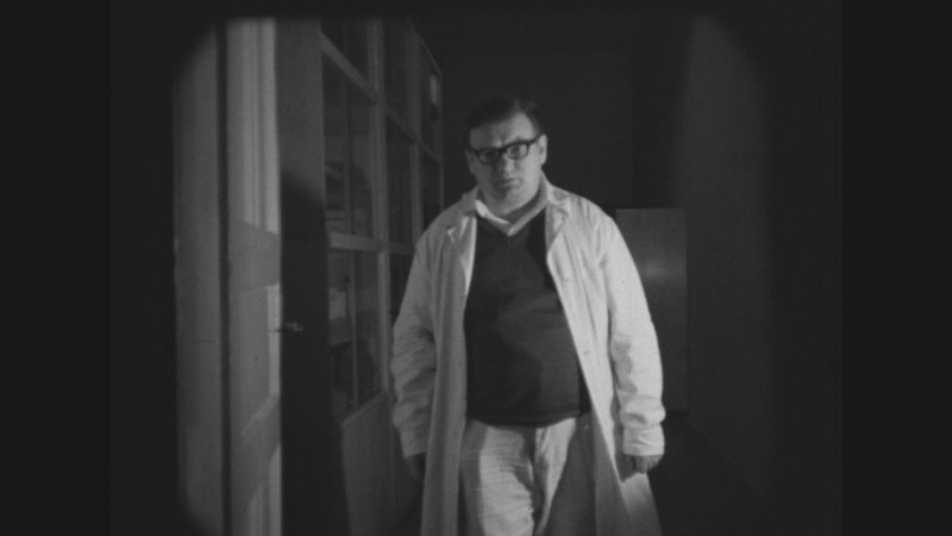

These exasperated pronouncements come from Vratislav Effenberger, leader of the post-war Czechoslovak Surrealist Group until his death in 1986, on the subject of his friend and fellow Surrealist Ludvík Šváb. Unfair though these offhand remarks might be (they were made in conversation with František Dryje), they anticipate something of the mix of sentiments we are likely to feel on first learning of Šváb. On the one hand we may be struck by the impressive range of his activities and enthusiasms: at various points or concurrently, Šváb was a jazz guitarist who performed and toured with the Prague Dixieland Band; a researcher for the Czechoslovak Film Institute; a critic, essayist and poet; a filmmaker, scriptwriter and photographer; and – his ‘day job’ – a psychiatric doctor based for the most part at the Research Institute of Psychiatry in Bohnice, Prague. On the other hand there is the curious lack of lasting or visible accomplishments, the seemingly paltry legacy in which this flurry of diverse pursuits resulted.

This seems especially true of Šváb’s work as a filmmaker, which easily casts him as a chronic underachiever to contrast with the prolific and accomplished oeuvre of his world-famous compatriot, animator Jan Švankmajer. Most of the film scripts that Šváb wrote, fairly modest as these projects were, went unrealized, and the bulk of what he did commit to film amounts to seemingly unstaged documentation of his friends and surroundings, holidays and travels. Evženie Brabcová – in an essay from an excellent, much-needed collection on Šváb recently published by the Czech National Film Archive – divides Šváb’s filmed output into the categories of ‘home movies’ (soukromé filmy – literally ‘private films’), ‘travelogue materials’ and ‘experiments’ or ‘studies’. Brabcová acknowledges that this is a ‘working’ categorisation, and indeed the experimental shorts and travel films easily blend into the home movies on technical grounds alone, with all Šváb’s films marked by the same crude features of the solo amateur: 16mm, no sound, sloppy framing, occasionally unstable camera and under-exposed film.[2]

But to write off Šváb the filmmaker as the ne’er-do-well of Czech Surrealism is to overlook the interest of his unfilmed scripts as texts, the wit, slapdash poetry and sardonic punch of his finished films, as well as the questions his work brings up about the relationship between film experiment and film document, between a text and its viewer-reader, between criticism and creativity. It is also clear that the technical limitations on Šváb’s work were in part deliberately chosen. As Jiří Horníček writes, Šváb suffered from no ‘excessive ambition’ as a filmmaker and saw amateur conditions as ‘the most conducive environment’ for his ‘approach to filmmaking’, enabling ‘direct authorial testimony’ without the mediation of actors or technical personnel.[3] ‘Partial deficiencies’ were accepted ‘as a natural part of the resulting work’, and the mistakes to which Šváb’s self-confessed technical ineptitude gave rise could even prove welcome for their revelatory or inspirational power.[4] This approach is of course consistent with the Surrealist disdain for aestheticism in the pursuit of authentic expression and with the movement’s classical receptivity to the revelations of chance.

Šváb’s ‘failure’ is such as to make us reconsider the desirability of success. Playful and mischievously appropriative, imperfectly realized when it is not simply unrealized, this is cinema in a proudly minor key, a seizing of the movie camera’s license to let this psychiatric doctor play the fool (something Šváb – ‘star’ as well as director of his productions – is given to doing onscreen). As such his work is not so far removed from that of more celebrated figures of international avant-garde and underground film – whether the autobiographical, diaristic drive of Jonas Mekas, the Surrealist détournement of cinema past in Joseph Cornell, or the home-made B-movie magic of Jeff Keen.

Cinema in a Typewriter

Born in Prague in 1924, Šváb had family roots in cinema. His grandfather was Josef Šváb-Malostranský, a cabaret performer and songwriter who also had the distinction of being ‘the first Czech actor whose performance was recorded by the film camera’ and of authoring the first three fictional films made in what is now the Czech Republic, a trio of comic shorts shot in 1898 by Czech cinema’s native pioneer Jan Kříženecký.[5] As Jiří Horníček notes, Šváb-Malostranský was an ‘inspirational model’ for his grandson, one to whom we might link Svab’s love of early cinema and his ‘lack of prejudice’ towards ‘so-called lowbrow genres’ like slapstick comedy, horror and adventure serials.[6] This stance is evident in Šváb’s critical and archival activity as well as in his own films and scripts, which tend to imitate the episode or gag formats of early cinema and draw on Gothic or mystery material.

Another crucial inspiration came from the Surrealist-oriented circle around Vratislav Effenberger, with which Šváb first made acquaintance in 1952 at the ‘premiere’ reading of Effenberger and Karel Hynek’s play The Last Will Die of Hunger (Poslední umře hlady).[7] From this point on Šváb ‘began to believe’ that the ‘interwar adventure’ of Surrealism was not over, and that its ‘sense of revolt’ lived on in a necessarily different, contemporary form, ‘less elevated’ and ‘more sarcastic’.[8] Effenberger and Hynek’s dramas, with their ‘agonising humour’ and ‘sneaky poetry’, were also the spark for Šváb’s own ambition to write plays and scripts.[9]

As Šváb notes, Effenberger and Hynek’s plays were designed to be read rather than seen. The same is true of most of the film scripts that Effenberger wrote solo – he tellingly described them as ‘pseudo-scenarios’ – and their realization would in many instances have proved costly and technically demanding had such been attempted.[10] By contrast, Šváb, who in the 1950s was already active in amateur filmmaking, really wanted to film the scripts he wrote, devising these short texts in such a way that he could realize them with the limited means at his disposal. Where, then, does his general failure to do so leave these scripts? Are they simply that – failures, unfulfilled dreams? In an essay entitled ‘Cinema in a Typewriter’, which Šváb published together with several of these unfilmed scripts a year before his death in 1997, Šváb concludes with the suggestion that ‘even the written form of the film experience can find its readers, who thanks to their imagination turn into viewers’, and that ‘if even something of what I wrote makes an impact, this would fulfill more than I could have expected’.[11] While such statements may simply reflect a stoic acceptance of unrequited ambitions, they are consistent with the Surrealists’ and avant-gardes’ long-standing interest in the film script as self-sufficient genre – a tradition into which Effenberger’s pseudo-scenarios fall – and with Šváb’s own emphasis on the role of the viewer’s imagination in the cinematic experience. In another essay, a contribution to an anthology of unfilmed (and predominantly avant-garde) screenplays, Šváb writes of ‘the screen in our head’, ‘far more suggestive’ than the actual screen and able to rouse text-bound scenes and images to life.[12]

On the page Šváb was free to translate his Surrealist sensibilities into a shifting stream of incidents, images and apparitions, and hence his scripts reveal an imaginative quality, even a flamboyance, that his realized films necessarily restrict or else channel into a laconic conceptualism. As Jakub Felcman observes, the scripts are evocative, perhaps to a surprising degree, of ‘classical’ Surrealist cinema.[13] Charting the familiar waters of dream, desire, dread and the double, they tend to work through a particular situation in ways that are mysterious, romantic, alluring and disturbing. His early script Untitled (Bez názvu, circa mid-1950s) was, by Šváb’s admission, even a variation on the ‘story’ of the lovers in Buñuel and Dalí’s Un chien andalou (1929), a further exploration of a relationship’s ‘twists’ and ‘transformations’. Šváb invents his own arresting images and sometimes approaches a Buñuelian cruelty: the male protagonist’s face covered in white grease, the Girl’s eyelid pierced by a fishhook, a bleeding bird pinned to a door with a knife. The 1958 Astarté is another oneiric male-female encounter, in which a crowded beach scene suddenly gives way to the unsettling appearance of the titular quasi-goddess – a thoroughly Surrealist, Ernstian hybrid of man and woman, human and machine, human and bird – who dominates and confounds the male protagonist with an oblique language of posture and dance. For Whom the Bells Tolls (Komu zvoní hrana, 1958) – one of two scripts intended to be part of a larger cycle called Golem – Mirror of Prague (Golem – Zrcadlo Prahy) – suggests a kind of Surrealist documentary of the Czech capital and its magical reverse side, where everyday crowds of consumers share space with an unexplained murder plot, a protagonist who lies prone in the street, a memorial ceremony with candles and ‘bridesmaids’, and another mysterious romance. Boundaries of the Zone (Hranice pásma, 1969), from an idea of Effenberger’s, is a Surrealist horror story of both exterior and interior threat, as a man on a banal bus journey discovers, first, that the vehicle is being pursued by wolves, and then finds his co-passengers uncannily transformed into large, hollow-headed puppets.

Certain bizarre elements in these scripts seem to push against the limits of filmic expression. At the beginning of Untitled, for instance, Šváb mentions a group of ‘OBJECTS’ (sic) that are meant to recur throughout the film, deliberately unspecified forms intended ‘to evoke an emotional reaction in the viewer’. These objects’ ‘special characteristic’ is ‘that they can be changed relatively easily into quite real objects, which correspond by means of their location to some everyday need’.[14] One wonders how successfully these objects’ intended emotional impact, as well as their switch back to ordinary functionality, would have been accomplished onscreen. This in turn prompts the question whether the indeterminacy permissible on the page does not serve this conceit better, by simply allowing us to imagine what the affecting but unnameable objects might look like. Similar comments might be made about the cinematic feasibility of capturing the hybrid nature of the formidable Astarté as described above, or of realizing the strange creatures that appear in The Hunts of Baron Karol (Lovy Barona Karola, 1979), homages to the fantastical, chimera-like figures of Surrealist painter Karol Baron. Perhaps that limitless projection screen of the mind was the natural destination for these texts after all.

One script of Šváb’s that actually engages directly with the challenge of realization is the 1962 Unfilmed… (Nenatočený…), a project that went through various stages of preparation, the last of which is a detailed treatment with technical instructions. Less obviously related to Šváb’s Surrealist concerns, this project seems rather to have emerged out of his participation in the amateur filmmaking community. The script’s protagonists are themselves a group of amateur filmmakers who meet up in a café to thrash out a proposed film project. The enthusiasts propound various ideas for their film, which are concurrently illustrated onscreen; these visualised extracts reflect their authors’ disagreements over style, mood and story. (One slightly risqué scene is thus modified after one of the filmmakers protests that this will not win the film any prizes from ‘moral’ and upstanding jurors.) The project ultimately founders, reflecting, in Horníček’s words, the absence of ‘real originality and invention’ or of ‘constructive collaboration’ among the group.[15] The group’s script, soiled with wine and offensive doodles, is literally abandoned in the café, then tossed into the rubbish by a cleaner, after which a final caption appears: ‘This film did not appear in autumn 1962 and it was not made by Janíček – Karlas – Rýpar – Šedivý – Šváb, – and you therefore did not see it, which is no bad thing.’[16] This is such a merciless cancelling out of a creative endeavour – with even the onscreen script condemned to physical oblivion – that Šváb’s own project perversely recuperates its own failure in advance: so thorough is the spirit of self-negation here that Unfilmed…’s actual non-realization seems merely like an extra punchline to the gag.

Filmmaking as Commentary

In 1971 Šváb shot three experimental short films: Ott 71, The (fully clothed) Nude Descending (and ascending) a Stair and L’autre chien. Modest as these shorts are – all run roughly between 40 seconds and two minutes and feature Šváb as their sole performer – they are the only deliberately staged or ‘artistically’ conceived works in Šváb’s filmography that seem to have been properly completed.[17] Ironically, these three actually realized films, all of which are variations of a famous work of film or art history, are among the most ‘textual’ of Šváb’s film projects: not so much remakes as commentaries or revisionist postscripts to the original works, these shorts are of a piece with Šváb’s critical writings on cinema.

All three films adopt the format of the routine or gag, evoking the self-contained, vaudevillian spectacles of the early cinema of attractions (as theorised by Tom Gunning). This connection is most explicit in Ott 71, based on Fred Ott’s Sneeze (1894), a five-second test film shot at the Edison laboratory and the oldest surviving film with a copyright. Edison’s ‘physiognomic film’, whose primary ‘attraction’ is the ‘unprecedentedly detailed view’ it offers of ‘facial grimacing’, exemplifies a period in which ‘motion pictures were perceived predominately as a new form of visual experience and […] a tool for producing new kinds of visual knowledge’.[18] Šváb’s revisiting of Edison’s film remains true to the sensibilities of early cinema, and indeed ups the particular attraction on show. First we see Šváb preparing a mix of salt and pepper and inserting it into his nose. This is followed by a woozy moment of apparent hypnosis and hallucination, with Šváb’s visions illustrated by cut-in and likely appropriated footage of carnival rides – images that make this return to the cinema of attractions forthrightly literal and provide a visual drumroll for the climactic physiognomic display. Šváb then tops the solitary sneeze of Edison’s original with a salvo of shuddering blasts.

Ott 71 can be seen as a playfully anti-aesthetic gesture and a debunking of cinema’s status. It is a literal return to cinema year zero, to a time when cinema was primarily both sensation and scientific instrument, prior to the consolidation of narrative and a developed cinematic language. Šváb’s film is a tribute to cinema before ‘art’, an insistence on the fundamental attraction of physiognomic and bodily display that has remained overt only in the most disreputable genres of film (Linda Williams, in her classic study of pornography, has situated Edison’s film at the origins of a history of cinematic ‘prurience’, in which Ott’s discharge figures as a prototype of the hardcore ‘money shot’).[19]

The (fully clothed) Nude Descending (and ascending) a Stair was described by Šváb as a polemic with Hans Richter’s cinematic recreation of Duchamp’s famous painting Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 (Nu descendant un escalier n° 2, 1912) in Richter’s full-length avant-garde film Dreams That Money Can Buy (1947). (More tenuously Šváb can be seen as returning again to the origins of cinema and to the medium’s role of producing new knowledge about physical reality, given the acknowledged influence on Duchamp’s painting of Marey’s chronophotography, a proto-cinematic experiment in the photography of movement.[20]) For the perceived ‘pomposity’ and aestheticism of Richter’s film, Šváb substitutes defiant, down-to-earth amateurism.[21] Duchamp’s ambiguously gendered nude is now incarnated not by the classical female figure seen in Richter’s film but by the clothed, middle-aged figure of Šváb himself, who repeatedly ‘follows himself’ up and down a staircase in a series of seamlessly matched shots. Whatever fluid grace the technique achieves is compromised by Šváb’s ungainly, effortful, slightly sped-up movements and by errant details or mistakes: Šváb scratches his head, stumbles, and at one point spoils the continuity of the joined shots by leaving his shoes behind on the stairs.

The (fully clothed) Nude can finally be considered a dialogue not only with Richter but also with Duchamp himself. Like Šváb’s film, Duchamp’s once-scandalous painting had itself subverted the classical trope of the nude, in his case by turning the human figure into a mechanical object. Šváb’s version, with its Sisyphean ascents and descents, retains a sense of the mechanical, suggesting a body bound to an absurd and ultimately insanely frenetic cycle of repetitions. Yet Šváb’s own anti-idealist ‘debasement’ of the nude also means emphasising the fallible and clownish – a touch of humanist saving grace?

L’autre chien, the wittiest and most ingenious of the three films, returns to yet another foundation point, to the quintessential Surrealist film that is Un chien andalou. Where Šváb had once elaborated on the themes and images of Buñuel and Dalí’s film in an apparently sincere manner in Untitled, his use of it in L’autre chien is more ironic and satirical. Šváb narrows his attention to a restaging of the original’s most notorious and iconic sequence. Šváb, like Buñuel in the original, looks out at the evening sky, and the familiar image appears of a ‘horizontal sliver of cloud’ cutting into the moon (achieved here by the most rudimentary of special effects).[22] But instead of the expected metaphoric complement to this image – the infamous slicing of a woman’s eyeball – Šváb tucks into a plate of fried eggs. By the most bathetic of analogies the oozing matter of the slit eye is replaced by the runny liquid of the sliced yoke.

In a brief written commentary on the film, Šváb described the substitution as a decline from the savage expression of ‘supreme freedom’ to the mere satisfaction of ‘insignificant everyday desires’.[23] To this extent the film is representative of the revisionist stance of post-war Czech Surrealism, which tended to problematise the liberationism of the movement’s interwar years and to displace the utopian vision for a more critical eye on the dysfunction and banality of the real. Šváb’s commentary also explains the play of verbal expressions that grounds the associations of moon, eyeball and egg. One Czech saying describes the full moon as shining ‘like a fish’s eye [rybí oko]’, and from rybí oko it is ‘only a step’ to volské oko – an ox’s eye or, in colloquial speech, a fried egg (the playful association with Un chien andalou is enhanced when one recalls that the slashed eyeball was reputedly that of a dead cow).[24] There is a characteristic (if here unintended) perversity in the fact that one of the few scenarios that Šváb was actually able to realize depends on wordplay and requires a written explanation to be fully appreciated. At the same time the film offers a reprise of the ‘physiognomic’ attraction of Ott 71, and the viewer does not require a knowledge of Czech colloquialisms to appreciate the climactic spectacle of a man eating an egg. An extreme close-up of Šváb’s gurgitating mouth and throat again indicates the camera’s capacity for enhanced ‘visual knowledge’ that was so prized and exploited by early cinema. Šváb can thus be seen as highlighting how much the avant-garde shocks of films like Un chien andalou owe to the ‘primitive’ cinema of attractions, even as he irreverently punctures the visceral transgression of classic Surrealism.[25]

These three concise shorts might seem to stand as the high point of Šváb’s cinematic achievements, but they also betoken an apparent wider failure, standing as the sole scraps of Šváb’s stated ambition to produce a whole series of films recreating ‘all the successful works of film history’.[26] As with Šváb’s unrealized scripts, though, the ‘failure’ of this project seems questionable: was such a series a real ambition of Šváb’s, or just a joke? In an introduction he wrote for the first private screening of Ott 71, Šváb’s inclusion of the name ‘Jára da Cimrman’ among the august filmmakers he wished to remake – a reference to the fictive all-purpose Czech genius of Ladislav Smoljak and Zdeněk Svěrák’s comic theatre – arouses heavy suspicions of leg-pulling.[27] In any case, is not failure an appropriate outcome for a project whose aim, by the evidence of the three films produced, was to be anti-aesthetic and deflationary?

Surrealist Homo Ludens

The ‘one man band’ aspect of Šváb’s film projects may have cast him here as a rather solitary figure, but no consideration of his work would be complete without placing it in the context of the post-war Czechoslovak Surrealist Group. Surrealism figured in Šváb’s work and life not merely as an inspiration, a storehouse of images and ideas, but also as a living and familiar presence, a collective endeavour, and a set of tight-knit personal bonds that were no doubt intensified by the virtual illegality – the genuinely ‘underground’ status – within which Surrealism operated throughout much of the communist period.

The strongly personal nature of this affiliation is evident in the frequent presence of Šváb’s Surrealist companions in his home movies, shown together drinking, talking, sunbathing, celebrating and goofing around. Šváb even extends this intimacy to his scripts, in which he sometimes pays tribute to his fellow Surrealists or even casts them as characters. His 1970 script The Death of Vratislav Effenberger (Smrt Vratislava Effenbergera), for instance, has the titular Surrealist leader sentenced to execution by firing squad (a reflection, no doubt, of the condemned position of the Surrealists in the newly repressive environment of early normalisation). In like fashion, Šváb himself makes an alarming appearance as a human snack dispenser in Jan Švankmajer’s film Food (Jidlo, 1992).

In deeper terms Surrealism pervades Šváb’s filmmaking as an integral spirit of play. While game-playing has always been a favoured tool of the wider Surrealist movement, it was the Czechoslovak Surrealists who elevated it to vital importance in the 1970s, as the group devised a series of bizarre games and playful collective experiments that were seen as a way to explore the imagination, enhance ‘mutual communication’ and reinforce the bonds of friendship.[28] Šváb’s critical, experimental cinema could be seen as embodying a similarly ‘investigative’ model of play, a ludic counterpart to the experiments he pursued as a professional psychiatric researcher. If we accept the conventional view of play as an activity in which process matters more than final product, seeing Šváb’s cinema as play helps us understand his lack of concern about the technical inadequacies of his films or the fact that they sometimes went unfinished. This may also help explain his predilection for the home movie, a form of filmmaking that Evženie Brabcová, citing film theorist Roger Odin, describes as an essentially process-driven genre, a means of ‘common play’ akin to ‘surrealist experimentation’ (it is thus unsurprising that Šváb’s ‘Surrealist family’ were often the participants in his home movies).[29]

If making home movies was one form of collective adventure, writing film scripts was another. In 1971 the Czech and Slovak Surrealists, using a method developed by Jan Švankmajer, embarked on a collective scenario-writing experiment that they dubbed Silent Mail (Tichá pošta), from the Czech name for the game ‘Telephone’. Using Effenberger’s 1959 ‘pseudo-scenario’ Nowhere No-one (Nikde nikdo) as their starting point, the 11 participants each produced a new version of the same scenario in turn, having access only to the version of the previous participant. Šváb not only participated in the game but also edited and commented on the final results, and indeed the experiment reveals certain connections with his approach as a filmmaker: firstly, as with Šváb’s experimental shorts, the project occupies a liminal territory between commentary and creativity, with each new version of the script a response to the last one as well as a work in its own right; and secondly, process is firmly privileged over completion, as Effenberger’s ‘finished’ 1959 script is subjected to a long and thus potentially infinite series of transformations whose interest lies above all in its play of ‘convergences and divergences’.[30] In contrast to Šváb’s chronicle of an amateur filmmaking project in Unfilmed…, where the collective effort at producing a coherent work had ended in dissension and failure, the collective experiment of Silent Mail permits a more candid display of differences as well as similarities in the authors’ ‘interpretative approaches’, senses of humour and imaginations.[31] Šváb’s version of the script is particularly revealing of its author’s sensibility, adding to the core situation of a nightmarish bus ride with an appearance by Feuillade’s pulp anti-hero Judex, a consequent shift into a detailed pastiche of silent films from ‘around 1915’, and even a swimsuit that had evidently once ‘belonged to [Šváb’s grandfather] Josef Šváb-Malostranský’![32] (The original title of Šváb’s contribution, Rendezvous at the Mill, or Werich Meets Judex (Dostaveníčko v mlýnici anec Werich se setkává s Judexem), was also partly a homage to one of his grandfather’s films.) Effenberger criticised such references as a retreat into ‘subjective infantility’ and a personal ‘film heaven’.[33] We might equally call them an origin story of Šváb the filmmaker.

This is how Effenberger characterised Šváb in 1977:

‘Whipped by the cruel sanctions on written or any other kind of expression, his

instruments fail. And thus instead of all that glittering poison that dissolves

into the air, we must content ourselves with the petty jokes of a slightly

“different dog” than the one we had just been admiring for its ability to play

with its remarkable quarry.’[34] We must finally qualify

this stern assessment. Šváb’s amateurish instruments may have failed; real

sanctions may have prohibited him in the transition from page to screen; and

his finished films may have been ‘different dogs’ that seemed merely to nip at

the heels of grander beasts. But his Surrealist imagination, perceptive critical

engagement and sharp, playful humour could never be fully muzzled.

Notes:

[1] Vratislav Effenberger, quoted in František Dryje, ‘Po požáru’, in Evženie Brabcová, Jiří Horníček (eds), Ludvík Šváb: Uklidit po mé smrti (Prague: NFA, 2017), p.310

[2] Evženie Brabcová, ‘Soukromé filmy Ludvíka Švába’, in Ludvík Šváb, p.129.

[3] Jiří Horníček, ‘Kinematografie pohledem Ludvíka Švába’, in Ludvík Šváb, p.112.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid., p.107.

[6] Ibid., p.108.

[7] Stanislav Dvorský, ‘Ludvík Šváb a jazz’, ibid., p.173.

[8] Ludvík Šváb, quoted in František Dryje, ‘Umět se ponořit (Podstatnost jako vedlejší produkt osobnosti a tvorby Ludvíka Švába)’, ibid., p.151.

[9] Šváb, ‘Vratislav Effenberger a Karel Hynek: Aby žili (1952)’, ibid., p.311; Šváb, ‘Kino v psacím stroji’, ibid., p.265.

[10] Karolína Zalabáková, O Vratislavu Effenbergerovi, jeho ztraceném díle a vydané próze, PhD thesis (Brno: Masaryk University, 2006), p.21. The fall of the communist system in 1989 did make the prospect of realizing these ‘unrealizable’ scripts less impossible than it might once have seemed. At least one of Effenberger’s ‘pseudo-scenarios’, The Brewers’ Revolt (Vzpoura sládků), has been staged theatrically, and Surrealist Group member David Jařab dramatised sections of these texts in his 2018 filmic portrait, Vratislav Effenberger, or The Hunt for the Black Shark (Vratislav Effenberger, anec Lov na černého žraloka). Šváb’s work, too, seems to have attracted professional interest during the early post-communist period: he recalls a company that was interested in producing his 1979 script The Hunts of Baron Karol (Lovy Barona Karola) for Košice television, but the project failed due to lack of money (‘Kino v psacím stroji’, p.267).

[11] ‘Kino v psací stroji’, p.267.

[12] Šváb, ‘Le cinéma impossible: předběžná skica k úvodu’, ibid., p.288.

[13] Jakub Felcman, Kino v psacím stroji: Fenomém fiktivního scénáře v českém prostředí, Master’s thesis (Prague: Charles University, 2006), p.83.

[14] Šváb, Bez názvu, Ludvík Šváb, p.268.

[15] Horníček, p.116.

[16] Šváb, Nenatočený… (Treatment k filmu), p.255.

[17] Šváb would mention another film that he shot in the same year, a ‘film loop’ called The Waltz of the Vampires – ‘inspired solely by the British distribution title of Roman Polański’s otherwise pretty obnoxious American film The Fearless Vampire Killers’ – but I have been unable to find any further record of this film (Šváb, ‘L’autre chien’, Ludvík Šváb, p.258.)

[18] Ana Hedberg Olenina, Psychomotor Aesthetics: Movement and Affect in Modern Literature and Film (New York, Oxford University Press, 2020), p.116.

[19] Linda Williams, Hard Core: Power, Pleasure, and the “Frenzy of the Visible” (Berkeley; Los Angeles; London: University of California Press, 1999), p.51-52, 101; Scott Bukatman, The Poetics of Slumberland: Animated Spirits and the Animating Spirit (Berkeley; Los Angeles; London, 2012), p.40.

[20] Pierre Cabanne, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp (London: Da Capo, 1979), trans. Ron Padgett, p.34.

[21] Horníček, p.114.

[22] Linda Williams, Figures of Desire: A Theory and Analysis of Surrealist Film (Berkeley; Los Angeles; Oxford: University of California Press, 1992), p.63.

[23] ‘L’autre chien’, p.258.

[24] Ibid.

[25] As Gunning writes, the cinema of attractions continued as ‘a never dominant but always sensed current’ that ‘can be traced from Méliès through Keaton, through Un chien andalou (1928), and Jack Smith.’ (Gunning, ‘The Cinema of Attraction[s]: Early Film, Its Spectator and the Avant-Garde’, in Wanda Strauven (ed.), The Cinema of Attractions Reloaded (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2006), p.387.

[26] Šváb, ‘Ott 71’, Ludvík Šváb, p.256.

[27] Horníček, p.114; ‘Ott 71’, p.257.

[28] See Vratislav Effenberger, ‘Poznámka k modelovému závěru Tiché pošty’, Analogon, no.41-42, 2004, p.42; Krzysztof Fijałkowski, ‘Invention, Imagination, Interpretation: Collective Activity in the Czech and Slovak Surrealist Group’, Papers of Surrealism, no.3, 2005, pp.3-6 (https://www.research.manchester.ac.uk/portal/files/63517387/surrealism_issue_3.pdf) (retrieved 11th April 2021); Jonathan Owen, ‘Films for the Drawer: Postwar Czech Surrealism and the Impossible Encounter with Cinema’, in Rebecca Ferreboeuf, Fiona Noble and Tara Plunkett (eds), Preservation, Radicalism, and the Avant-Garde Canon (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), p.244.

[29] Brabcová, p.132.

[30] Effenberger, ‘Poznámka k modelovému závěru’, p.42.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Šváb, Werich se setkává s Judexem (volná variant ana variant M.S.), Ludvík Šváb, p.284-285.

[33] Effenberger, ‘Poznámka k modelovému závěru’, p.44.

[34] Effenberger, ‘O Ludvíkovi Švábovi’, Ludvík Šváb, p.307.