In the 1920s, actor and director Karel Lamač was among the few truly respected film personalities in Czechoslovakia. In 1925, the daily Český deník called him an artist whose work already guaranteed him a spot in the Pantheon of Czech cinema but who still had much more to offer.[1] Lamač was seen as a versatile artist and praised for his technical, aesthetic, acting and literary skills. The text also stresses that if we want to see more Czech films of exceptional quality, securing funds is an absolute necessity. Which is an obstacle Lamač and many short-lived production companies had to surmount. Despite the stabilisation of the industry and the increasing number of cinemas, domestic productions were still considered risky.

Period press had made it a habit to criticise Czech films, but between 1924 and 1925, the situation changed. In 1925, Film magazine published an article titled New Era of Czech Film.[2] It describes the increasing quality of local production with technical and narrative qualities reaching their peak. The titles listed as examples included the dynamic comedy Catch Him! (Chyťte ho, 1924), sometimes screened with an alternative title The Clumsy Burglar (Lupič nešika). The film was directed by Lamač, who also had the leading role, produced by AB and distributed by Gloriafilm. Catch Him! was premiered on 1 January 1925 and was promoted as an excellent new-year comedy.[3] In many aspects, it represents an inspiring intersection of the questions to what extent should Czech films resemble foreign productions and to what extent they should rely on their distinctiveness.

Devotion to New Art

In his memoirs, Václav Wasserman, a screenwriter and one of Lamač’s closest collaborators, confirms the increased interest in Czech films and praises White Paradise (Bílý ráj, 1924), a film which the distributors and cinema owners doubted would perform well.[4] According to Wasserman, it was only thanks to Lamač’s heroic and almost self-destructive efforts that the film made it through postproduction and appeared in the cinemas (it was premiered on 1 August 1924). He describes the busiest actor and filmmaker of his time – Lamač regularly worked abroad – as a passionate, ambitious and most of all steadfast artist. Lamač’s devotion to film is apparent from his short publication How to Write Film Libretto (Jak se píše filmové libretto) from 1921, where he lists several fundamental aspects and rules, whether he learned them somewhere or discovered them himself – several examples are given from The Lumberjack (Drvoštěp, 1922), which was his first preserved directorial project. Lamač wanted to adopt the style of Hollywood. He wrote dramatically tight narratives based on causality, the editing followed logical continuity and alternating scene sizes follow the ‘Griffith’ method. A compact and tight dramatic form was the most important element. Another repeating element in his silent films is the criminal motif he shared with several other filmmakers, some of whom – for instance, Martin Frič and Přemysl Pražský – continued working with him throughout the 1930s. But Lamač’s work stands out from the period production. His rigorous replication of American models was an exception. The film production back then was dominated by episodic and cyclical narratives. Catch Him! is a clear creative continuity. Lamač was commissioned with this project after he finished White Paradise, which was sold to UFA for international distribution. He managed to finish it in the four remaining months of the same year. It was the very first time the legendary ‘big four’ got together – director and leading man Lamač, leading lady Anny Ondráková, cinematographer Otto Heller and screenwriter Václav Wasserman. The First Republic film industry was built mainly on personal relationships and friendly groups of specific ‘creative groups.’ With each person listed above, Lamač fostered fruitful domestic and international collaboration.

Narrative Ambition

Wasserman described the film as a variation on Harold Lloyd’s slapstick comedies. Before this film, Lamač appeared in comedies by Karl Anton, who regularly made slapstick comedies. He also made the situational comedy Gilly in Prague for the First Time (Gilly poprvé v Praze, 1920) where he explicitly cited and imitated Charlie Chaplin and the famous Keystone Cops. Chase scenes were an inseparable part of (not only) American slapsticks, and the dynamic action intertwined with surprising interaction with the environment was the main source of humour. Catch him! utilises the same and tested formula.

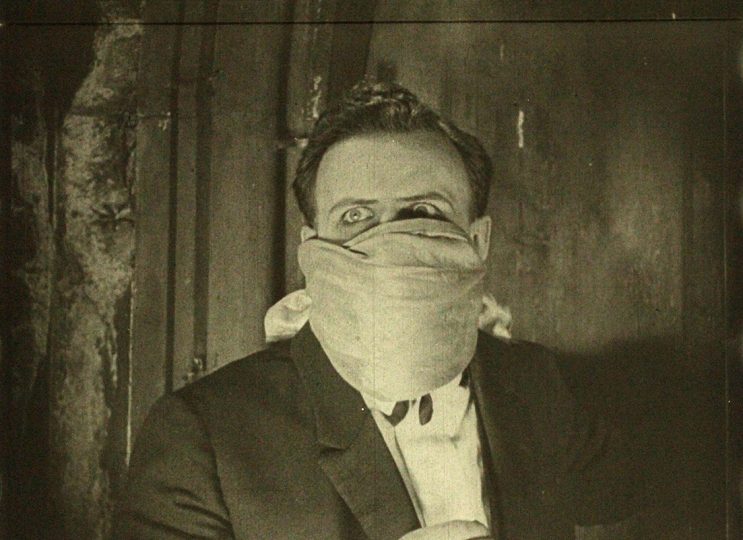

The film tells a straightforward and simple story of a man, the sculptor Johnny Miller, who wagers that even after a night out with his friends, he can find his way home blindfolded. Before he knows it, he unwittingly joins a group of robbers and is caught burgling the house of a wealthy man and his ward. He spends the following day trying to escape and rectifying the situation while facing one twisted and absurd situation after another. It’s a clever comedy filled with well-written mistakes and confusions. The film defies its local nature – the characters have American names, the main villain has the now deplorable ‘blackface,’ the settings are universal and the film tries to come across as cosmopolitan. The attributes of Harold Lloyd’s work can be traced in the protagonist. Johnny is a victim of external situations. He’s only very rarely proactive. It’s his friends who reveal his true identity to the ward Lilly, who takes a liking to him. Johnny simply tries to adapt even to the most tumultuous situations, which forms the basis of individual gags. But when he takes matters into his own hands, he’s immediately caught. Johnny spends the climax of the film paradoxically tied to a railway crossing barrier and is saved from the villains by an unconcerned railwayman. The force which helps to free Lilly from the hands of the villains in the end is actually the police force. Johnny is only ‘present.’ That’s an entirely different scheme than in The Lumberjack, where Lamač’s protagonist takes on the role of the hero and saviour. His ambitious work with the main character further underscores Lamač’s thorough use of foreign patterns. His work with layers and linking individual gags with the visual framework is particularly impressive. The compositions create contrasts by combining the depth of field and two-dimensional movements. The position of the camera is always defined by the possibilities of the visual gag. Lamač and Heller were fully aware of the importance of the vantage point and its impact on the portrayed action.

The film economically and ingeniously utilised all the outlined motifs and props. Everything pays off. The comedy of errors and accidents is thus organic and smart, like well-organised chaos. The rhythm and tempo of the narration escalate along with the situations the hero finds himself in. It all climaxes with a parallelly edited sequence in which we see Lilly fighting the goons and Johnny tied to the railway barrier. Lilly isn’t a typical damsel in distress waiting to be saved: she actively tries to escape. The chases and the hero’s confused blindfolded march – the bases of the film’s comedic construction – are shot on locations. Lamač used everything he could from shrubberies to a junk shop window to a phone booth. A variation on a ‘Keystone’ chase is naturally also included. While the police are ridiculed in the first part of the film, they deliver justice in the finale. Lamač’s approach to slapstick and Hollywood genres in general can be compared with the poetics of Oldřich Lipský. Their intention wasn’t ridiculing foreign models. They tried to reinvent them and interpret them in their own way.

Hard to Please

The press usually praised Lamač’s mastery both in front of the camera and behind it, but it’s important to look at the way the media tried to put the film in the context of Czech cinematography. For instance, the daily Právo lidu was quite harsh.[5] It described Lamač’s attempt to recreate an American hit as an absolute failure and mere shadow of its perfect inspiration. The text calls for Czech films to be purely Czech as they cannot compare to world-class films. Another point of the criticism was that the film pretended to be something American and renounced its local roots.

The traditionally damning Lidové noviny, where the Čapek brothers also published their scathing texts about Czech film industry, joins in the criticism. The daily appreciates the technical prowess and sees it as a step forward. But it mentions the dismal state of the Czech film industry and calls for abandoning international themes and subjects. Purely Czech themes and methods are allegedly enough to win recognition.[6] Lamač used foreign methods and patterns in his previous films, but this is the first time author of the text, J. Sheriff, criticises him for it. It’s hard to say whether it’s because Catch Him! was deliberately promoted as a foreign adventure.

It seems that most critics don’t mind the foreign narrative and stylistic patters, but rather the fact that the story lacks local elements. After the film’s premiere, Lidové noviny published one more review.[7] It says that the film is an embarrassing attempt with outdated humour and a disgrace to Prague. The author also objects to the amorality of certain characters and the fact that we’re trying to present viewers with a gag which has intoxicated Lamač wander about Prague Castle. It says the film lacks taste. But it also admits that if some scenes were cut out, it would be a simple comedy, which is something Czech filmmakers should strive for. Paradoxically, the text doesn’t see any problems with the film drawing inspiration from American film.

Večer daily, on the other hand, praises the film monumentally and describes it as a sensational comedy.[8] “The authors managed to learn a lot from American comedies. In fact, their film is so good that we can safely say: why should we buy American films, if we have Czech films of the same quality?” The often ambivalent reception of the film is at least as interesting as the film itself. Quite paradoxically, Karel Lamač subsequently focused on purely Czech stories. The following year, he adapted The Lantern (Lucerna, 1925), The Good Soldier Švejk (Dobrý voják Švejk, 1925) and together with Theodor Pištěk made a biographical film about Karel Havlíček Borovský (1925) and a comedy based on a local play The Countess from Podskalí (Hraběnka z Podskalí, 1925).

To this day, Catch Him! is a remarkable film embodying a certain period dogma. It is a testimony to the constant search of the true form of Czech film, mainly from the audience. We know from some period advertising and cinema programmes that it was still screened in the 1930s. [9] And although it’s somewhat overshadowed by other Lamač’s films, it highlights his ambition and endeavour to introduce international poetics.

Catch Him! (Chyťte ho!, Czechoslovakia, 1924), director: Karel Lamač, script: Karel Lamač, Václav Wasserman, cinematography: Otto Heller, cast: Karel Lamač, Anny Ondráková, Theodor Pištěk, Antonie Nedošinská, Martin Frič, Bedřich Veverka, Vladimír Majer, Jan W. Speerger et al. AB, 36 min.

Literature:

L. Marek, Lamač Karel 1897–1952. Iluminace 32, 2020, no. 1, pp. 135–138.

R. D. Kokeš, Česká kinematografie jako regionální poetika. Otázky kontinuity a počátky studiové produkce. Iluminace 32, 2020, no. 3, pp. 5–40.

Václav Wasserman and Rudolf Mader, Václav Wasserman vypráví o starých českých filmařích. Prague: Orbis 1958.

Jiří Horníček, Gustav Machatý – Touha dělat film. Brno: Host 2011.

Jaroslav Brož and Myrtil Frída, Historie československého filmu v obrazech 1898–1930. Prague: Orbis 1959.

Notes:

[1] Český deník, 10 February 1925, no. 40, p. 5.

[2] Film: Orgán Svazu kinematogr. industrie ČSR v Praze, 1 August 1925, no. 8, p. 1.

[3] Zpravodaj Zemského svazu kinematografů v Čechách. Prague: Zemský svaz kinematografů v Čechách, 1 December1924, no. 15, p. 7.

[4] Václav Wasserman and Rudolf Mader, Václav Wasserman vypráví o starých českých filmařích. Prague: Orbis 1958, p. 249.

[5] Právo lidu: časopis hájící zájmy dělníků, maloživnostníků a rolníků, 25 October 1924, no. 247, p. 2.

[6] Lidové noviny, 31 October 1924, no. 548, p. 3.

[7] Lidové noviny, 7 January 1925, no. 11, p. 3.

[8] Večer: lidový deník, 25 October 1924, no. 246, p. 6.

[9] Český Lloyd, 31 January 1931, no. 9, p. 2, Moravský deník, 21 April 1933, no. 94, p. 2, Národní osvobození, 31 October 1930, no. 300, p. 8.