A footnote can sometimes lead to a surprising discovery. Scrapbook of the Sixties: Writings 1954–2010 by Jonas Mekas contains, among many other texts, an author’s interview with the American documentary filmmaker Emile de Antonio. De Antonio mentions there that he discovered some of the archive documents for what is probably his most famous and controversial film, In the Year of the Pig (1968), during a visit to Prague. The translator Andrea Průchová Hrůzová then specifies in a footnote that the materials were most probably obtained in the Prague branch of the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam (NLF),[1] which was formed in late 1960 and early 1961 together with the military units called the Viet Cong.

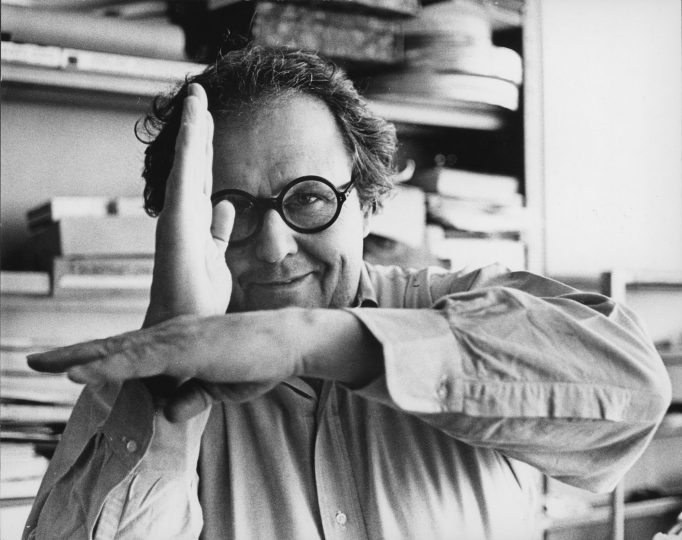

Emile de Antonio (1919-1989) was a unique personality of American documentary filmmaking. He studied at Harvard, where, as a child of a bourgeois family, he was first introduced to leftist ideology. He was expelled from school for his troubled behaviour and from 1938 earned a living as a labourer on the Baltimore docks. During the Second World War, he participated in bombing of Japan as a US Army pilot. After the war, he was part of the New York avant-garde. He met John Cage, Robert Rauschenberg, and Andy Warhol about whom he wanted to make a documentary for Czechoslovak television.[2]

De Antonio did not establish himself as a filmmaker until he was in his forties, when he and Dan Talbot edited television footage of Senator McCarthy’s speeches to create the political documentary Point of Order (1964). In the following years, he specialized in dismantling state power through the ironic recontextualization of available archival footage. In doing so, he avoided off-screen voice-overs. In making his “found footage” films, he followed the dialectical tradition represented, for example, by the Soviet filmmaker Esfir Shub. He drew new meanings by combining both fictitious and news archival footage from many sources.

This is how the documentary In the Year of the Pig, a sweeping chronicle of the historical causes, progress and contemporary reflection of the Vietnam War, was made as well. Completed in 1968, the film was nominated for an Academy Award. De Antonio set the war conflict in the context of the history of colonialism, American political corruption, and media manipulation of public opinion. He did not resort to emotional testimonies of war veterans or footage of the suffering Vietnamese (as Peter Davis did a few years later in his Oscar-winning Hearts and Minds). He made do with a montage of archival footage that had not been used until then, not only in the US but in many cases abroad as well.

While the U.S. Department of Defense refused to give de Antonio access to its archives, Europe accommodated the filmmaker. Prague was one of his stops during the thorough searches conducted in 1967 and 1968. He told Mekas about his visit there in 1969, and later also spoke about it during a two-day symposium at the University at Buffalo: “I procured enough money, went to Europe, and got footage from France. The NLF headquarters was in Prague, Czechoslovakia. I went to Prague and got their footage. I went to East Germany. The East Germans have the best film archive in the world and I got everything I wanted from them…”[3]

The director’s stay in Czechoslovakia is documented by his application for a Czechoslovak visa as well as by his correspondence with the cultural institutions that facilitated his visit. These materials are preserved in his personal archive at the University of Wisconsin–Madison Archives.

As confirmed by historian Ondřej Crhák of the Faculty of Arts, Charles University – whose dissertation focuses on Czech-Vietnamese relations – the Prague office of the NLF not only existed but was also the very first official representation of the Vietnamese resistance in the Eastern Bloc. Its activities began on 1 November 1963 with the approval of the Czechoslovak government. The office published its own bulletin with reports on the fighting in Vietnam and mediated contacts with foreign countries through local embassies. Its work, however, had to adhere strictly to the political line of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia and, by extension, to the foreign policy of the Czechoslovak Republic. The reward for this conformity was full coverage of its operating costs.

In 1965, according to Crhák’s research, the Prague office was expanded and renamed the NLF Representation. This new status brought increased financial support (amounting to 300,000 Czech crowns) and the right to use its own flag, as well as to maintain contact with foreign embassies and the media. Crhák emphasizes that the Prague Representation of the NLF held one of the strongest positions not only within the Eastern Bloc but globally. When Czechoslovakia recognized the Provisional Revolutionary Government of the Republic of South Vietnam in June 1969, the Prague NLF Representation was elevated to the status of an official diplomatic mission.

It can be assumed that these circumstances significantly facilitated de Antonio’s access to film and television footage of the Vietnamese resistance – material that was otherwise inaccessible to Western filmmakers. His stay in Prague, however, was not confined solely to the research for his forthcoming documentary.

According to his biographer Randolph Lewis, de Antonio was scheduled to attend a meeting with local filmmakers, including Miloš Forman, who reportedly expressed his criticism of the U.S. policy in Vietnam to his American colleague.[4] American journalist David Leff, then working as a correspondent in Czechoslovakia, was to interview de Antonio for Radio Free Europe. The rest of de Antonio’s days and evenings in Prague were spent drinking wine in bars, conversing with students, and “admiring beautiful young women, although his eagerness was tempered by the presence of his fourth wife, Terry Moore.”[5] De Antonio’s guide in Prague was allegedly the novelist, party functionary, and StB collaborator Jiří Mucha.

The most important outcome of de Antonio’s stay in Prague was, in any case, his access to the rare archival materials – resources he likely could not have obtained without the vibrant exchange of information and intellectual capital that linked the American anti-war left with the socialist states of the 1960s, Czechoslovakia among them, through the framework of left-wing internationalism. What might appear as a marginal episode in the career of a single artist was, in fact, part of a broader and remarkable cultural-political phenomenon – one that warrants closer investigation.

Bibliography:

Emile de Antonio & the New York Art World. Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. Available online at: <https://wcftr.commarts.wisc.edu/index.php/exhibits/emile-de-antonio/emile-de-antonio-the-new-york-art-world/> [cited 11/06/2025]

Bruce Jackson, Conversations with Emile de Antonio. Senses of Cinema. Available online at: <https://www.sensesofcinema.com/2004/politics-and-the-documentary/emile_de_antonio/> [cited 11/06/2025].

Douglas Kellner, Emile de Antonio: A Reader. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press 2000.

Randolph Lewis, Emile de Antonio: Radical Filmmaker in Cold War America. University of Wisconsin Press 2000.

Jonas Mekas, Zápisník z šedesátých let. Praha: Artmap, 2025. // Scrapbook of the Sixties: Writings 1954–2010. Leipzig: Spector 2019.

Alan Rosenthal, An Interview with Emile de Antonio. Film Quarterly vol. 32, no. 1, 1978, p. 4-17.

Notes:

[1] Jonas Mekas, Zápisník z šedesátých let. Praha: Artmap 2025, s. 303. (Scrapbook of the Sixties: Writings 1954–2010.)

[2] Emile de Antonio & the New York Art World. Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. Available online at: <https://wcftr.commarts.wisc.edu/index.php/exhibits/emile-de-antonio/emile-de-antonio-the-new-york-art-world/> [cited 11/06/2025]

[3] Bruce Jackson, Conversations with Emile de Antonio. Senses of Cinema. Available online at: <https://www.sensesofcinema.com/2004/politics-and-the-documentary/emile_de_antonio/> [cited 11/06/2025]

[4] Randolph Lewis, Emile de Antonio: Radical Filmmaker in Cold War America. University of Wisconsin Press 2000, p. 85.

[5] Ibid, p. 86.