„It was supposed to be a film about an athlete, a female athlete. I wasn’t interested much. But then I realized that the banality and certain uniqueness of the topic, resulting from its distinctiveness, actually provides the most specific, almost schematic subject matter for a charged parable about the meaning and value of a human sacrifice, and that its primitive tangible materiality can become a substrate for a general drama, a human drama of an eternal struggle, a struggle for immortality amidst the finite human powers.“[1]

With these words, Věra Chytilová described in the director’s explication her feature film debut, Something Different (O něčem jiném). This drama of two women who never meet was, however, already her third film released in Czechoslovak cinemas.

In 1961, she graduated from the Academy of Performing Arts (FAMU) in Prague with her dissertation film Ceiling (Strop). In this honest psychological study, the main heroine interrupts her medical studies to pursue the attractive career of a model. When it doesn’t meet her expectations, the young woman becomes disillusioned. Chytilová’s film reflecting the climate of the time with reportage-like immediacy was followed by A Bagful of Fleas (Pytel blech, 1962). In it, she approached the sociological probe into the environment of apprentices as a staged documentary accompanied by the uncensored voice over of a young worker.

Both films had in common the topic of the individuals‘ relationship to an environment defining the boundaries within which they can find some fulfilment. From March 1963, they were screened together in a short-story diptych, There’s a Bagful of Fleas at the Ceiling (U stropu je pytel blech).

In the meantime, Ladislav Fikar from the production team Šmída – Fikar offered Chytilová to direct a film based on a screenplay by František Kožík. It was inspired by the life of the gymnast Eva Bosáková – the mentor and athletic role model of Olympic champion Věra Čáslavská. As described by the director in the explication above, she wasn’t really impressed by the subject matter. No wonder. Such films of the time usually unilaterally celebrated the extraordinary performance of athletes without considering the toll they were paying for their success. These were works of propaganda meant to attract young people to sport.

That’s why, contrary to custom, the promising filmmaker decided also to portray the frustration accompanying the extraordinary achievements. She first went to a gymnastic sports camp in Nymburk to speak to Bosáková and find out about her „joys and sorrows“.[2] After this consultation, she demanded the subject matter be reworked. First of all, Chytilová added another main heroine to be able to take a larger perspective on being a woman. In the film, the life of a talented athlete is contrasted with the life of a housewife. Neither feels fulfilled.

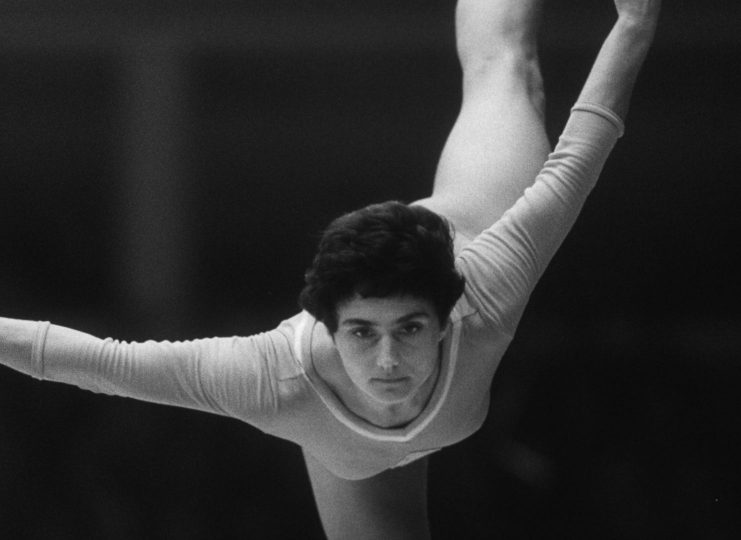

The poetry of Věra Chytilová’s early films was inspired by cinéma vérité. In addition to professional actors, she cast non-actors playing themselves. The dialogues are often improvised. The film is not shot in the studio but rather on authentic locations. The standard analytical cuts bringing the viewer to diegesis are replaced by impartial, detached observation. The inherent tension of Something Different is achieved through a combination of veristic methods depicting aestheticized scenes of gymnastic training and „artistic“ creations of graphic and sound parallels between the two stories.

The veristic approach is reflected in casting Eva Bosáková in the role of her fictitious alter ego. Furthermore, Věra Uzelacová, who already played a minor part in Ceiling, plays her namesake. The border between actress and role is made even thinner by casting Uzelacová’s actual son Milivoj in the role of her film child. Both Bosáková and Uzelacová were then allowed to use their own words in the dialogues. Chytilová only asked them to convey the gist.

In an interview with Jiří Janoušek, Eva Bosáková described the director’s work with the actors: „I don’t know if you can call it improvisation, but she very often stepped aside and accommodated me. When we disagreed on how to perform an action, especially when I struggled with her version, she told me to do it my way and only stick to the message.“ [3]

In defiance of filmmaking under the doctrine of socialist realism (with its black-and-white point of view, classic narrative style and schematic characters), the Czechoslovak New Wave was truthfully recording everyday private problems rather than portraying big dramas. Everyday activities and common human interactions make up a significant part of the footage of Something Different. However, both are presented with an extraordinary eye to detail of speech and action.

Věra’s mainly cleans the family apartment, prepares meals and attends to her son’s and husband’s needs. Eva spends most of her time training in the gym. Both women’s lives are marked by a fatiguing repetition of similar, seemingly purposeless movements. As such, the film narrative is not a causal chain of causes and effects, but rather several layers of fragments portraying conditions and situations that are somewhat typical. Chytilová then takes this method to the extreme in her next film Daisies (Sedmikrásky), which is even more subversive towards the traditional narrative.

Almost everything Věra does relates to her household, husband or son. Several scenes are composed just of her doing household chores. When in one such scene she opens and closes kitchen cabinets with mechanical regularity to put in or take out various pots and plates, she reminds one – just like the heroes of silent comedies – of a machine controlled through a programme, and not expressing her free will. Věra’s accelerated movements shift the focus from the preparation of the meal itself to the monotonous and absurd nature of her actions. We clearly see that even though the cyclic, repeated actions might ensure the functioning of the household, they certainly don’t lead to inner fulfilment.

With her movements, Eva tries to follow her trainers‘ orders. The symbolic meaning of the training sequences is similar to that of Věra’s scurrying around the kitchen. Both women fulfil the implicit or explicit requirements of someone else. However, Eva’s movements are not as utilitarian as Věra’s. They have an aesthetic function at the same time. When at the beginning of the film the gymnast stretches her tired feet, the scene is much gentler than the following shot with the camera in a similarly low position, where Věra smooths out the carpet with her feet and shakes off her slippers. Chytilová works with similar contrasts throughout the entire film.

Even though the narrative style of Eva’s story is reminiscent of a live-action documentary, the cinematographer Jan Čuřík portrays her floor exercises as precisely geometrized compositions with the gymnast’s black leotard contrasting with the gym’s white walls. The shots of Bosáková exercising on the beam taken from a vertical view remind one of abstract shapes. At the same time, the film takes into account that it takes hard, exhausting training and a lot of self-denial to produce such elegance, drawing a parallel between Eva’s and Věra’s movements without mechanically connecting their stories.

The stories of both women intersect only once, at the beginning of the film, when Věra’s son watches a sporting competition in which Eva is taking part. However, the shots on the screen only present the final effect, and not the fear and fatigue the gymnast must overcome daily. If Věra is attracted to the life of Eva or of the models in the fashion magazine she leafs through before going to bed, it’s only because she only sees the surface glamour and not everything hidden behind it.

The conflict between Eva’s public and private roles is also revealed in her interview with a journalist, who interrupts it as he realizes just how empty the phrases are behind which the woman hides her true nature. Only off the record does Eva express her uncertainty and the sadness of her unfulfilled emotional life. She only smiles for the cameras – the means for creating her image. Eva’s storyline culminates with the Gymnastics World Championship, which also starts with a shot of Eva’s smile.[4] If success tends to be associated only with happiness, then through Chytilová’s eyes, it is the result of pretence and the media’s distortion of reality. The idea of perfect womanhood represents an unachievable construct.

What will remain there for Eva when she achieves the objectives set out, ends her sports career and her other – successful but to an extent only illusory self – ceases to exist? The film ending suggests she would pass on her experience to the younger generation. But at the same time, wouldn’t she pass on the pattern leading to her entire life being consumed by sport? The idea that Eva basically doesn’t exist outside of the sports framework is supported by the aspects of her life that the film focuses on.

Chytilová either leaves out her private life completely, or only considers those parts of it related to gymnastics (for instance, listening to music in a free moment makes Eva think about a routine she could perform to that piece). We don’t learn much about how she lives outside of the gym, what she thinks about, and what she feels. In contrast, Věra, as a woman finding fulfilment only in her family and marriage, is portrayed mainly while doing household chores and embarrassing moments of married life. Even though this approach probably doesn’t faithfully reflect the reality, it serves well the intended moral message.

We find out more about Věra’s emotional life so as to realize how alienated she feels in her marriage. She doesn’t have a chance to find fulfilment outside of it and duplicate her identity through her media image. Considering her type of character, her escape takes the quite logical form of an extramarital affair. But this also soon becomes yet another tiring stereotype leading to nowhere. Věra finds herself trapped in the relationship with her lover just like she has been limited by tending to her husband. She stays with her husband even when she learns he has been unfaithful to her as well. In other words, her characterization is limited so that she can serve for Chytilová as a model of a woman who cannot imagine her life without a partner from whom she derives her identity.

Jan Žalman aptly noted that „Something Different had all the features of a laboratory experiment with diametrically different test subjects.“[5] Nevertheless, the differences between both women, made even more pronounced through the focus only on certain aspects of their existence, bring to the fore the topic of female self-fulfilment Chytilová wanted to explore. Even though the two women‘ s stories never intersect and the viewers themselves are instructed – through continued movements in consecutive shots, sound bridges and music leitmotifs – to look for similarities between them for themselves, the film takes different paths only to come to the same conclusion.

Both Věra and Eva wish for their lives to be about something different as well (besides marriage/gymnastics). However, their doubts whether they can achieve that given the ceilings set by their partners, trainers, society and their own personal decisions are more pronounced at the end of the story than at the start. Věra has no objective she would strive to achieve. Eva has nothing but this objective.

The film, portraying stories of two women to make us more generally think about how to live a life we wouldn’t regret, was awarded as the best debut at the Mannheim Film Festival in autumn 1963. After this reviving impulse, discussion and writing about new film and its authors in Czechoslovakia increased. So, paradoxically, the Czechoslovak film miracle, which was „at best“ marked by ignoring the female perspective and at worst by open chauvinism, had its seeds in a film very female in its perspective, narration and topics.

P. S. Eva Bosáková spoke about the filming and reactions to the film in 1968 in the Mladý Svět weekly. These are some of her answers:

„I don’t know if you know Ms Chytilová – it was crazy, there was no screenplay, I had to do what she said, exercise while thinking about the acting. When I saw the first previews, I told her I wouldn’t do it anymore. Ms Chytilová talked me out of it, and then it was very interesting, and I am very happy I did it and experienced it. […] The film won in Mannheim, and this led to more very interesting work for me. I was travelling with the film across the countries where it was screened – West Germany, Finland, Poland, Italy… It was a bit strange. I was there as a film star, participated in the Q&As after the screenings, smiled during the cocktail parties, and then the next morning I would lead a gymnastics training in my sweatpants. […] Only the slap we shot only once. It wasn’t supposed to be there, but we were so into the scene with Luboš Ogoun that wham – and all of a sudden there was a slap. Only three of us knew the slap might be there, so everyone around us was left dumbfounded, and very soon I heard all over Prague that Ogoun was slapping me.“[6]

Something Different (Czechoslovakia, 1963), director: Věra Chytilová, writer: Věra Chytilová, cinematography: Jan Čuřík, music: Jiří Šlitr, starring: Eva Bosáková, Věra Uzelacová, Josef Langmiler, Jiří Kodet, Milivoj Uzelac Jr., Jaroslava Matlochová, Luboš Ogoun, Vladimír Bosák et al. Filmové studio Barrandov, 81 min.

Notes:

[1] Kopaněvová, Galina, Neznám opravdový čin, který by nebyl riskantní. In Ulver, Stanislav, Film a doba 1962–1970. Praha: Sdružení přátel odborného filmového tisku, 1997, p. 23.

[2] Pilát, Tomáš, Věra Chytilová zblízka. Praha: XYZ, 2010, p. 130.

[3] Janoušek, Jiří, Simultánní interview s Evou Bosákovou a Věrou Uzelacovou. Kino, No. 21 (10/ 10), 1963, p. 3.

[4] Filming took place during the actual Gymnastics World Championship taking place in Prague. The rest of the film was made later, and that’s why Bosáková had to fake imperfections and insecurities during the scenes of her training for her winning performance.

[5] Žalman, Jan, Umlčený film. Praha: KMa, 2008, p. 118.

[6] Dobiáš, Jan, O Evě Bosákové. Mladý svět, No. 2, 1968, p. 5