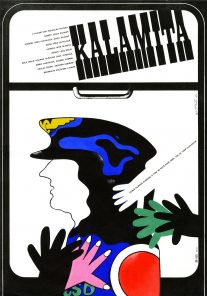

After an enforced seven-year break, Věra Chytilová could start directing feature films again in 1976, when she made The Apple Game (Hra o jablko). Instead of at Barrandov Studio, she was allowed to make her sarcastic sociological probe at Krátký film. We will only find Barrandov in the credits of Panelstory or Birth of a Community (Panelstory aneb Jak se rodí sídliště, 1979) and Calamity (Kalamita, 1980), which were essentially made in parallel. All three films were marked by difficulties in their development, shooting, and screening. Nevertheless, they still resonated very well with audiences despite their limited distribution, thanks to being uncompromisingly critical of the moral distortion of both the individual and society.

Like Panelstory, Calamity is an amusing parable with elements of civic satire. Instead of jumping back and forth between several characters inhabiting one space-time, here the narrative focuses on one protagonist – a young graduate who starts working for the railways. Honza (Bolek Polívka) has not yet internalized the rules of the new environment, and his juniority underscores the conformism and stereotypes governing the lives of his superiors and colleagues.

Rendered without much psychological depth, Polívka’s novice is rather an observer who is only settling in and mirroring the different moral stances of people he meets. With his disorientation, unpreparedness, and slight defiance of the constricting rules, he gradually exposes the incompetence of the management, and the system’s resulting malfunctioning. Even though most people he encounters complain about the status quo, they do nothing to change it.

Everything starts with the door handle left in Honza’s hand when he first comes to work („Before I realized it, I was no longer lucky“), and also the subsequent episodes making up the plot in a relatively loose order are smaller or larger calamities. The narrative is not only fragmentary, it is also disrupted by the frenetic shooting, insertions of short cutaways between longer, clear shots and omitting breaks between shots. Before one scene ends, another one with a new action starts.

Like the other films by Věra Chytilová, Calamity doesn’t give us a moment’s peace to simply sit back, follow the causal chain of events and enjoy the witty lines exposing the emptiness and ineffectiveness of the slogans of the time („traditions must be observed“). With its ability to „mobilize“ the viewer, it is different from the comedies of the same period with a more traditional narrative style, which didn’t rip the viewers out of their conformist position, but rather reassured them with its form that nothing was amiss and it was all right as such.

The test whether Honza would stand in the new working environment culminates with his first ride at the end of the film. During the ride, the train is buried under an avalanche. The minor personal calamities are suddenly interrupted by one from above going beyond the individuals and compelling them to leave the positions they had comfortably settled in. The stuck passengers lose their tempers and inhibitions, exposing different mechanisms of dealing with a crisis through their actions (or passivity, for that matter).

The failing communication, inability to seek a constructive solution and poor work ethic, elements of which we have witnessed throughout the film, are now turning against the characters. Some people panic, some complain about the disruption of their comfort, others passively wait to be saved… luckily, a handful of people realize one cannot rely on external help. Assuming responsibility, they organize their own rescue operation. The first to be brought to safety over a bridge of human bodies are children, symbolizing in the last shot a chance for a new, better beginning.

If the characters make it out alive in the end, they do so despite the system, and not thanks to it. In the film where the individual scenes are connected through parallels rather than causalities (Chytilová already used this narrative style in her debut Something Different (O něčem jiném, 1963)), it is no surprise that this is a variation of an earlier situation. When early in the film Honza wants to order beer in the dining car, the arrogant waiter cuts him off saying he first had to have a meal. A woman sitting close to him, who has already eaten, thus orders beer for the entire car. In a world of meaningless, limiting rules, the only hope is solidarity and self-sufficiency – even if only in relation to a bottle of beer. This was true during the normalization period (1968–1989), just as it is today.

The dining car scene follows after Honza’s walking through the train during the opening credits, with close-ups of passengers eating their own food. These are deliberately exaggerated images of „healthy earthlingness“[1], the concept of which Chytilová was constantly criticizing in her normalization-era works. In the consolidated normalization society, moral ideals and personal freedom are subordinate to the requirement of a peaceful life and happy consumption.

Selfishly putting themselves first, everyone is indifferent to public affairs at least until they start interfering with their peace. Honza views the omnipresent cynicism and opportunism with amusement and stays on top of it. It seems that for the young hero, having casual flings is enough to „fulfil himself“, at least sexually. For a member of such an apathetic society, there is no other painless form of revolt and return to one’s authentic self.

—

Based on a newspaper article about a train buried under an avalanche in the United States, the Calamity screenplay was a „shelf warmer“ in the Barrandov studio. When the main Czechoslovak film dramaturgist Ludvík Toman offered it to Chytilová, he might have hoped that she would refuse the challenging winter shooting as well. However, he underestimated the filmmaker’s determination.

In any case, Chytilová demanded several changes to the original subject matter, which celebrated the heroism of the Public Security forces in saving all the passengers in the end. The working environment remained preserved; however, contrary to other normalization films, in Calamity this does not only represent the conditions and relationships in a particular workplace, but rather any failing management system; for instance, the state.

The director shifted the emphasis to Honza and his relationships, mainly with women. His romantic fumbling around reflects his search for a role in life in which he could find satisfaction, even fulfilment:

„I essentially saw the story as an account of his day: he starts a new job and is getting familiar with it. He meets several people who either like him or don’t, and the same is true for the girls he encounters. The original screenplay had a happy ending; I rather focused on the train – I was interested in this environment as I am very familiar with it, coming from a railway station. So, I included this in the film and I even cast my uncle, who was an innkeeper just like my father and had an attachment to railways.“[2]

Calamity was made in Miroslav Hladký’s dramaturgic team. Divided into five phases, the film was shot over the winters of 1978 and 1979. Even though Chytilová was working with the technical screenplay, including all critical comments and censorship interventions, she didn’t strictly adhere to it and let the actors – who, in the spirit of the New Wave veristic approach, were a contrastive mixture of professionals and non-actors (among them was the jazz trumpet player Laco Déczi) – improvise.

In addition to the weather and either too much or too little snow, the shooting was also disrupted by illnesses. The flu gradually disabled basically the entire crew, which was used as a pretext by the Barrandov studio to interrupt the shooting. It was because Bolek Polívka was supposed to film Ballad for a Bandit (Balada pro banditu, 1978) in Karlovy Vary, which had to be produced before the Karlovy Vary Film Festival. During the enforced break, Chytilová started filming Panelstory. Only when it was finished did she complete Calamity. When she presented the final edited version, the censors requested several changes. The director only agreed to half of them. She managed to defend the rest despite the problematic ideological message.

Taking into account the high costs of winter filming and deferred shooting, the Barrandov studio management had little choice but to release the film to recover the costs. Even though released without an advertising campaign – and in the Rudé právo daily, Jan Kliment condemned it for its ugliness and negativism – viewers took every opportunity to see it. The counter-reaction was not long in coming, and the screening of Calamity was forbidden in Prague.

The management of the nationalized film industry acted like the man in the buried train asking the woman sitting across from him to silence her child, who was innocently asking: „When are we going to die in this grave?“ Věra Chytilová was also seen as a persona non grata as she repeatedly preferred the truth over comfort and was saying things others didn’t want to hear, minding their comfort.

Martin Šrajer

Notes:

[1] Viz Jaromír Blažejovský, Jaromír, Zdraví pozemšťané. Tři poznámky k duchovním souřadnicím normalizační kultury. In Kopal, Petr. Film a dějiny 4. Normalizace. Praha: Casablanca; Ústav pro studium totalitních režimů 2014. pp. 377–396.

[2] Tomáš Pilát, Tomáš, Věra Chytilová zblízka. Praha: XYZ 2010, p. 227.