The first international success of our post-war cinema was the award that The Strike (Siréna, 1947) received at the Venice International Film Festival. This social drama about miners from Kladno who go on strike represented the best of the short period between the nationalization of the film industry in 1945 and the Communist coup three years later.

After the war, both the number and quality of films produced in Czechoslovakia decreased. High standards were upheld mainly in the case of literary adaptations, which comprise almost a third of the post-war production. A prolific author of that era was director Otakar Vávra, who made films such as Zikmund Winter’s Mischievous Bachelor (Nezbedný bakalář, 1946) and Karel Čapek’s Krakatit (1948). Jiří Slavíček adapted Gogol’s story in the horror film Portrait (Podobizna, 1947), and Jiří Krejčík’s debut A Week in the Quiet House (Týden v tichém domě, 1947) was based on Neruda’s collection of short stories Tales of the Lesser Quarter (Povídky malostranské). Also Karel Steklý attracted attention by adapting a book.

The former stage manager of the Liberated Theatre (Osvobozené divadlo), who wrote gags for Jiří Voskovec and Jan Werich in the 1930s, established himself in the Barrandov Studios as a screenwriter during the war. His work was often picked up by director Martin Frič. Under his artistic supervision, Steklý made a mining drama titled The Breach (Průlom, 1946) following the social trend of Czechoslovak film (e.g., Battalion [Batalion, 1937], Dawning [Svítání, 1933], Such is Life [Takový je život, 1929]). The historically first title produced by the nationalized film industry was based on Jan Morávek’s story set in the 1860s. With its theme revolving around a period dispute between wealthy townsfolk and poor miners, Breach indicated Steklý’s future artistic orientation.

Class conflict is also the main theme of the novel Siréna by Czech novelist and Communist journalist Marie Majerová in 1955. Much to her disappointment, Steklý chose only two chapters from this mosaic multi-generation story of the Hudec family from Kladno. Besides, Majerová wanted to emphasize dialogues, while Steklý preferred an elaborate visual concept. In his mind, the film wasn’t supposed to be chatty; it was supposed to resemble the “crack of a whip.” In the end, his vision prevailed.

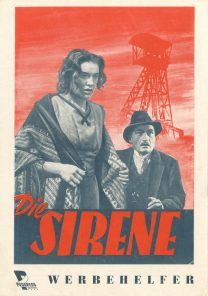

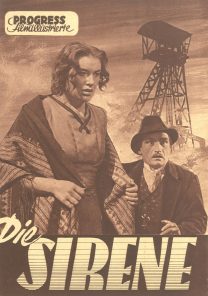

Steklý’s second look back at the history of the workers’ movement is set at the end of the 19th century. The heroes of this social ballad are Kladno miners who go on strike because of low wages and poor working conditions. They are joined in their protest by employees of the city’s steelworks. But the conceited mine owner turns to the military for help. Eventually, young Emča Hudcová becomes a tragic symbol of the hardships of the exploited working class.

Thanks to expressive cinematography by Jaroslav Tuzar, oppressive music by E.F. Burian and editing inspired by the Soviet montage theory, the compelling story about the problems of the working class suggestively creates the atmosphere of the industrialised city of Kladno. Steklý managed to intertwine moving individual dramas with a social dimension drawing attention to exploitative practices of ruthless businessmen while also stylistically uniting images, music and sounds.

Even though the film follows the doctrines of social realism, and the division of roles is rather straightforward, it is characterised by restrained expression, authentic portrayal of the environment and a civil approach to characters. Unlike the heroes of later dramas starring builders of socialism, the workers from The Strike, who now and then act as if governed by animal instinct, are not poster boys. In terms of acting, particular praise was given to the naturalistic performance of Marie Vášová, who portrayed mother Hudcová.

In Czechoslovakia, The Strike premiered in April 1947. About six months later, thanks to a screening at the 8th Venice IFF, the rest of the film world learnt of its existence. But the film was included in the festival competition at the very last moment. It wasn’t featured in the first selection. Czechoslovakia was represented by Tales by Čapek (Čapkovy povídky, 1947) directed by Martin Frič. Only at the behest of a member of the Czechoslovak film delegation, A. M. Brousil, was a copy of Steklý’s film hastily sent to Italy. The Strike appealed to the jury and audiences alike thanks to its internationally comprehensible social themes and mature film language, and eventually won the Golden Lion. In addition to the festivals’ Grand Prize, it also received the award for Best Score.

The two awards from a prestigious international event turned the film into a political tool used as a proof that the nationalised film industry was highly developed. Also Steklý’s following films were to be noticeably political – apart from his two Švejk films, he made also Darkness (Temno, 1950) and Anna the Proletarian (Anna proletářka, 1952). In the case of the latter, the most prominent motif is no longer an intimate atmosphere, but rather Communist ideology.

The National Film Archive now presents the digitally restored version of The Strike in cinemas. The film was restored in studios UPP and Soundsquare. The source material was the original negative on a black-and-white Agfa nitrate stock. The damaged or missing frames were replaced by a combined duplicate positive and a combined duplicate negative. The sound was taken from the original negative.

All NFA materials include an opening caption “Československý film uvádí” (Czechoslovak film presents). This caption was added to the negative as the state-owned company Československý státní film (Czechoslovak State Film) was established by the Government decree no. 72/1948 Coll. valid from 23rd April 1948, while The Strike was premiered in April 1947. Before the establishment of Czechoslovak State Film, all films were made by Československá filmová společnost (Czechoslovak Film Company). After the establishment of CSF, replacing opening captions in older films became a common practice.

This means we know the original wording of the caption but not its design. By comparing opening captions from other Czech films made in the same period, however, it was found that each opening caption was unique and didn’t have a unified design. The original caption in the Czech version wasn’t preserved in any of the available materials. So, a decision was made to remove the added caption and replace it with black frames.

Martin Šrajer