When the French surrealist leader André Breton, in a 1935 lecture, famously dubbed Prague the ‘magic capital of old Europe’, he captured that mythic, mystic image of a city long known for its fostering of eccentricities and abundance of bizarre legends. This is the Prague that Italian Bohemist Angelo Maria Ripellino would call ‘a breeding ground for phantoms’ and ‘an arena of sorcery’, a city stalked by ghosts and Golems, peopled by ‘strange commandos of alchemists, astrologers, rabbis, poets, headless Templars, Baroque angels and saints’.[1] A shadowy yet colourful realm, stocked to bursting with arcane secrets and amazing spectacles, the world of Prague myth would seem to be a rich, virtually inexhaustible repository for cinematic fantasies. And yet the magic face of the Czech capital has yielded a surprisingly paltry body of films, not least in Czech cinema itself. Exceptions include the silent Faustian short The Man Who Built the Cathedral (Stavitel chrámu, 1919), Julien Duvivier’s 1936 French-Czechoslovak production Le Golem, Martin Frič’s much-loved classic The Baker’s Emperor and the Emperor’s Baker (Císařův pekař – Pekařův císař, 1951) and the ludic, ironised contemporary take of Jan Švankmajer’s Faust (Lekce Faust, 1994).[2] The monstrous clay figure of the Golem, as known from the Prague legend of 16th century Rabbi Judah Loew, has also been adopted and remoulded by a range of foreign filmmakers, from the German Paul Wegener in his celebrated silent productions to the Polish Piotr Szulkin in his dystopian 1980 Golem.

One rare local work that plunges headfirst into the treasure-trove of magic Prague is the 1968 Prague Nights (Pražské noci), a joint directorial outing by Jiří Brdečka, Evald Schorm and Miloš Makovec. Writing of the film before its release, Brdečka, the film’s principal screenwriter and its apparent originator, himself observed the lack of domestic films that exploit the capital’s ‘unfalsified romantic atmosphere’, its store of ‘half-poetic, half-spooky legends’.[3] He remarks, however, that Prague Nights was born not from a desire to pay back the ‘debt of honour that our cinema owes to the stone fairy-tale on the Vltava’, but simply from his own enchantment with such material: ‘I love spooky stories and Prague ones in particular’.[4] Brdečka was after all noted for his attraction to the fantastic and had been a co-writer on The Baker’s Emperor and the Emperor’s Baker. But where the latter film essentially put its evocation of the Prague Golem in the service of a comic political fable, Prague Nights is more concerned with these legends’ sinister potential. This film thus has the added distinction of being a rare Czech foray into gothic horror cinema – even if, in this as in other ways, its success is only partial.

As such Prague Nights is as close as we will ever get to a Czech contribution to that enormous revival of horror cinema across Europe, the US and elsewhere that began in the late 1950s and would still be going strong into the 1980s. The film is akin to Britain’s contemporaneous Hammer productions in its gothic and traditional trappings, its rich décors and costumes, while it equally evokes the films of rival British studio Amicus in its anthology format and its morality-play structure in which wrongdoing characters are dealt nasty comeuppances.[5] A further point of comparison might be Masaki Kobayashi’s extraordinary Japanese film Kwaidan (1964), another horror anthology that decks out national folklore in lush gothic style.

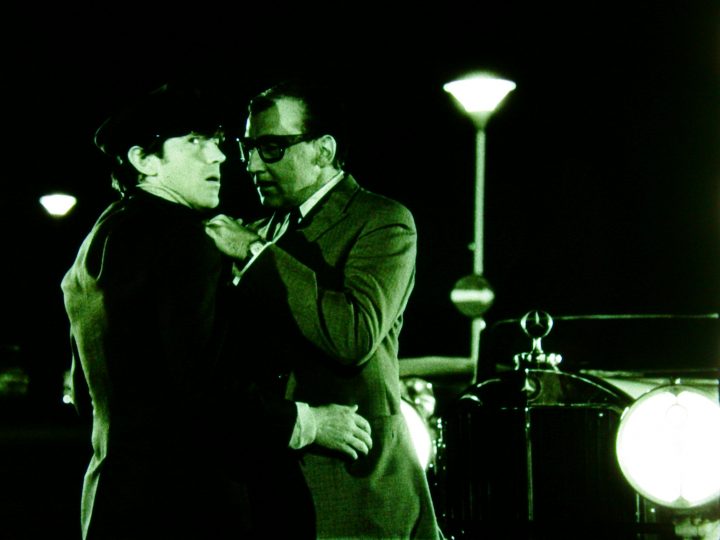

In grand horror anthology tradition, Prague Nights features a framing narrative in which acts of storytelling initiate the various episodes. Here the framing story (directed by Miloš Makovec) concerns Miloš Kopecký’s foreign businessman Fabricius, staying in Prague to close an important contract. Fabricius’s exact nationality goes unmentioned, but no matter: this pencil-moustached, sharp-suited and stylishly-spectacled foreigner is the archetypal Western businessman, emblem of a world of affluence and mobility (as underlined by his residence at the International Hotel, with its sleek modernist interiors and BOAC brochure displays). Fabricius hastily concludes his business engagements, energised with thoughts of sexual adventure, and, after his attentions are rebuffed by the young hotel receptionist, he strolls out into the Prague night.

Fabricius thus has something of the nocturnal flaneur who probes the mysteries of the metropolis in pursuit of ‘pleasure and hedonism’.[6] The tradition of the flaneur was notably transposed to Prague by an earlier foreign visitor, poet Guillaume Apollinaire in his story ‘The Stroller of Prague’ (‘Le Passant de Prague’), and taken up by the major Czech poet Vítězslav Nezval in works like ‘The Prague Walker’ (‘Pražský chodec’). Of course, Kopecký’s lecherous jet-setter makes for a rather tawdry and prosaic incarnation of this great literary and avant-garde archetype. Fabricius’s first stop is Prague’s world-famous Astronomical Clock, where he encounters, and is addressed by, the mysterious, alluring Zuzana (Milena Dvorská). This encounter establishes early on the film’s identification of Woman with city, the latter represented by perhaps its most iconic and easily identifiable landmark. The personification of Prague as a woman – often a ‘tempting and treacherous’ one who spells a protagonist’s downfall – is a long-running trope of Prague-based literature, and Brdečka and his collaborators fuse this literary convention with the dark myths of old Prague.[7] The stories that follow all feature predatory female figures who symbolise the city’s allure and danger, its enchantments and deceptions.

Zuzana herself becomes Fabricius’s guide to the ‘old things’ of Prague (without revealing at this point that she is one of those old things herself), and amid the gravestones of the Old Jewish Cemetery she introduces the first of three stories, as the film shifts from black-and-white into colour. The first story, ‘The Last Golem’ (‘Poslední Golem’), is the one most firmly grounded in actual Prague history, being set around the court of Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II, that eccentric, melancholy patron of art, science and hermetic knowledge from whose reign much of Prague’s magic reputation springs. After Rabbi Loew (Josef Bláha) refuses the Emperor’s request to recreate his legendary Golem Yosele, Rudolf commissions another Golem from the sinister, unscrupulous Rabbi Neftali ben Chaim (a characteristically intense, sneaky turn from Jan Klusák – who also wrote the score for the film’s next episode). Loew now embarks on his own esoteric project to thwart Neftali’s plans, exploiting as he does so his knowledge of Neftali’s greatest weakness – his sexual appetite.

This story, which Brdečka directed himself, is probably the strongest of the three (or four, if we include the framing narrative), at least in audio-visual terms. Its cramped world of vaults, chambers, doorways and passages admirably evokes the hermetic, secretive environment of Rudolf’s court, and the giant, looming Golem Neftali creates is an impressively monstrous presence, if ultimately a rather inert and passive one – the real agent of danger comes in a more unsuspecting and appealing form. Zdeněk Liška’s lush and evocative score, while unsurprisingly an asset to the film as a whole, plays a particularly effective role in this story, as the composer’s trademark use of chanting vocals presents an eerie siren song for the lustful Neftali. Another distinction of this episode, one of content rather than style, is the story’s overtly Jewish subject matter – this in the context of a national cinema in which the representation of Jews, the specificities of their historical experience and culture, was still unusual, and had even been a taboo subject during the previous decade.[8]

From Rudolf II’s brooding Renaissance-era court, the film’s second story, ‘Bread Slippers’ (‘Chlebové střevíčky’), takes us to the rococo refinements of the 18th century. This is a time of war and besiegement for the city, but the mood is frivolous and teasingly erotic, as a silly, self-centred countess (played by Polish actress Teresa Tuszyńska) kisses her chambermaid and flirts with her suitor, the Knight Saint de Clair (Josef Abrhám). The playful tone soon darkens though as the countess’s caprices reveal a true moral vacancy: after a boy is caught stealing bread from her kitchen, she learns that bread is ‘worth its weight in gold’ among the war-blighted poor, and, in knowing bad taste, she opts to have a pair of bread slippers made for an upcoming costume ball.[9] That evening a mysterious, uninvited figure (a suave Josef Somr) arrives to fulfill her request, a contract in hand. On the night of the ball the countess is whisked away by coachmen in grotesque white masks to the mystery man’s ominous residence, and it is here – in Faust’s former house – that she has to meet the contract’s infernal obligations.

‘Bread Slippers’ is the most fully developed of all the stories, and the only one concerned with any kind of moral or social commentary (there is something of the moral fable in the story’s closing image, when the fateful slippers finally turn back into two full, wholesome loaves of bread). These elements are perhaps unsurprising given that the director of this story was Evald Schorm, known for grappling with ethical and political questions in celebrated New Wave films like Courage for Every Day (Každý den odvahu, 1964) and Return of the Prodigal Son (Návrat ztraceného syna, 1966). Yet this episode arguably fails to fulfil the visual and dramatic potential of its material. Most notably, the story’s climactic dance of damnation, in which the countess is partnered with those souls whom her ruthlessness and irresponsibility had in one way or another condemned to death, could have been a passage of macabre beauty akin to Powell and Pressburger’s The Tales of Hoffmann (1951) or even the vampiric ball of Polanski’s The Fearless Vampire Killers (1967). But the scene does not have quite the required intensity, dynamism or visual outlandishness to truly enthrall.

The third story ‘The Poisoned Poisoner’ (‘Otrávená travička’), also directed by Makovec, is the shortest and slightest episode. Lacking dialogue altogether and narrated entirely in song, this mediaeval tale of a beautiful innkeeper who poisons her wealthy suitors with the help of a devoted male servant is more in the nature of an ironic sketch or, as one critic put it, an ‘anecdote’.[10] Besides its pleasing mediaeval and orientalist finery and some creative use of colour filters, there isn’t a lot here beyond a crescendo of cute twists, as the lethal seductress vies with and then falls for a fellow poisoner, with both finally falling victim to the woman’s besotted accomplice.

As we return to the framing narrative, Zuzana – the film’s storyteller and Fabricius’s night-time companion – is herself revealed to be the soul of the poisoned poisoner (with both figures played by Milena Dvorská), who has since been sentenced to eternity in hell and is now only allowed a brief sojourn above ground every 190 years. The continuity set up here between episode and frame story is not exactly organic. What is consistent though is the theme of harsh moral retribution which rears its head again in the frame story, which ends with Fabricius himself condemned to infernal servitude for his lust-driven romantic insincerity.

Just like Fabricius and Zuzana, who finally exit in a burst of flames and billowing smoke, Prague Nights essentially disappeared quickly after its release. Intended by Brdečka to be first and foremost a popular entertainment, the film evidently failed to connect with local audiences.[11] If we accept Jan Bernard’s assertion that the film was ‘created predominantly for export, with the aim of promoting this city…and attracting more foreign tourists’, it seems not to have fulfilled its purpose, making little mark internationally.[12] Among domestic critics the film received a tepid response, neither disastrous nor really enthusiastic. Miloš Fiala, in Rudé právo, noted that the film is ‘intelligently made’ and yet ‘will probably not take [the viewer’s] breath away’, while Kinokritika’s Gustav Francl judged it ‘unexciting and boring’.[13] Drahomíra Novotná, in Filmové a televizní noviny, ranked it among those commercial entertainment films that court their viewers with ‘cheap attractiveness, so-called “folksiness” and covert or overt pandering’, and cited its cautious helpings of horror and sex; in a supreme example of grudging praise she conceded that, while she was not scared, neither was she unentertained – even if the entertainment was not always of ‘the same intensity’ (this review, incidentally, prompted a public riposte from Brdečka, who objected that Novotná had mischaracterised him as a crude populist dismissive of ‘boring’ artistic films).[14]

Sadly these critical opinions have not proven drastically wrong with fifty-plus years’ distance: Prague Nights is no lost classic in need of redemption. Francl’s review, for instance, while unduly harsh, is not incorrect to point out that the film fails to do justice to the enticing subject matter of Prague myth, and this failure applies at both a deeper and a more superficial level. In deeper terms, the film lacks any of that genuine sense of mystery or strangeness with which, say, Švankmajer’s films imbue similar material – that arcane logic of celestial correspondences that infused the work of Rudolf’s court astronomers, the profusion of multiple levels of allegory in the bizarre mannerist art of court painters like Arcimboldo, or the cryptic psychological realities of a later Prague writer like Gustav Meyrink. With such seductive avenues of exploration on offer, the film’s repeated arcs of moral comeuppance seem all too pat and conventional. Meanwhile the paraphernalia of magic Prague is too often merely dropped in like passing sights on a city walking tour – here is Arcimboldo, here Rabbi Loew’s grave, here a retinue of humanoid-automaton servants – rather than being plumbed for its disturbing depths. At a more immediate level, these stories also lack that authentic sting of misanthropy, that bracing sense of true nastiness, that enlivens the most memorable of the Amicus films. The film never quite dares to betray its light tone and become a real horror film, but neither does it really aim for – or succeed as – comedy. Particularly exemplary of this tonal uncertainty is the framing story of Fabricius and Zuzana, which is arch and sardonic without ever being actually funny.

For all these shortcomings, however, Prague Nights does deserve credit for striking out into a seldom-explored area of national genre cinema, and for doing so with little obvious derivation from foreign horror traditions. It is to be admired too for resisting the full flight into parody that tended to be Czech cinema’s default move when tackling ‘Western’-style genre material (this refusal is all the more surprising given that Brdečka, together with Miloš Macourek, was the unchallenged master of parody).[15] But perhaps what makes this film of most interest to the contemporary viewer has little to do with horror conventions and rather more to do with the glimpse offered here of a proto-globalised Prague seen through the eyes of a foreign, specifically Western traveller. This is, in other words, a premonition – or, in ‘magic Prague’ terms, a clairvoyant foretaste – of the tourist-dominated, business-friendly Prague that would emerge with the fall of communism. After all, it is this later, post-communist Prague that would make the most relentless use of the city’s dark legends and magical image, enlisting their seductive power to capture foreign tourists as surely as Zuzana ensnares Fabricius (the fate suffered by this hapless businessman makes this Prague the ultimate tourist trap). From amidst the commodified legends of the present we can perhaps even derive a certain spiteful pleasure from the fact that in this film the ‘old things’ of magic Prague are no harmless tourist trinkets but prove capable of genuine dark magic, and finally demote this moneyed traveller to the role of an eternal chauffeur.

With

the passage of time, then, this rare experiment in Czech horror has become as

interesting for its inadvertent as for its intentional magic. The film may only

be fitfully successful in bringing to life the myths of Prague’s past, but it now

also compels as a sharp retroactive comment on the city’s future.

Notes:

[1] André Breton, Manifestoes of Surrealism, trans. Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1969), p.255; Angelo Maria Ripellino, Magic Prague (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1994), p.6.

[2] Le Golem and The Emperor’s Baker both have their roots in the 1931 musical play Golem, by the comedy duo of Jiří Voskovec and Jan Werich. In the case of Le Golem, however, director Duvivier rejected Voskovec and Werich’s own script for a more ‘straight’ horror-dramatic approach. The Emperor’s Baker, which Werich cowrote and starred in, is in the comic spirit of the original play. On the subject of Czech Golem films, it is also worth mentioning animator Jiří Barta’s sadly uncompleted adaptation of Gustav Meyrink’s novel The Golem (1915), begun in 1991. (See Adam Whybray, The Art of Czech Animation: A History of Political Dissent and Allegory (London; New York: Bloomsbury), p.194.)

[3] Jiří Brdečka, ‘Pražské noci’, Kino 23, No. 26, 26.12.1968, p.2.

[4] Ibid.

[5] One year before Prague Nights was made, Hammer’s regular production partner Seven Arts made its own stab at a film about the Prague Golem, Herbert J. Leder’s British-based horror It! (1967).

[6] Alfred Thomas, Prague Palimpsest: Writing, Memory, and the City (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2010), p.115.

[7] Ibid., pp.116-117; Ripellino, p.8.

[8] Marie Koldinská, ‘Rudolfínská doba v českém historickém filmu’, in Petr Kopal (ed.), Film a dějiny (Prague: Lidové noviny, 2004), 172; Tatjana Lichtenstein, ‘“It’s Not My Fault That You Are Jewish!”: Jews, Czechs, and the Memory of the Holocaust in Film, 1949-2009’, Dapim: Studies on the Holocaust 30, No. 2, 2016, p.125.

[9] This story was clearly inspired by the Prague legend of Countess Černínová – one of a number of Czech myths about proud nobles having bread shoes made and being supernaturally punished for it. (See Ripellino, p.180; Jan Soukup, ‘České pověsti o střevících z těsta’, Český lid 10, No. 3, 1901, p.210.)

[10] Jan Kliment, ‘Pražské noci’, Tribuna 1, No. 19, 21.5.1969, p.14.

[11] Brdečka, ‘Pražské noci’, p.3.

[12] Jan Bernard, Evald Schorm a jeho filmy. Odvahu pro všední den (Prague: Primus), pp.114-116.

[13] Miloš Fiala, ‘Pražské noci’, Rudé právo 49, No. 107, 8.5.1969, p.5; G. Francl, ‘Pražské noci’, Kino 24, No. 10, 15.5.1969, p.12.

[14] Drahomíra Novotná, ‘Dva ze středního pásma’, Filmové a televizní noviny 3, No. 8, 17.4.1969, p.4; Jiří Brdečka, ‘List Drahomíře’, Filmové a televizní 3, No. 13, 25.6.1969, p.4.

[15] Interestingly, the horror genre did not benefit from the Czechoslovak film industry’s policy of cultivating a more generically diverse, entertainment-oriented during the 1960s and ‘70s. In the 1970s, at least, the dearth of horror films was attributable in large part to the restrictive moral-ideological criteria of the normalisation era. (See Martin Šrajer, ‘Murders: the Czech Way. Czechoslovak detective films (II)’, Filmový přehled, 5.6.2017 (https://www.filmovyprehled.cz/en/revue/detail/murders-the-czech-way-czechoslovak-detective-films-ii); Tomáš Gruntorád, ‘Zombie, Vampire and Psychopath: On the History of Shelved Normalisation Horrors’, Filmový přehled, 5.6.2017 (https://www.filmovyprehled.cz/en/revue/detail/zombie-vampire-and-psychopath-on-the-history-of-shelved-czech-normalisation-horrors).)