Can this ironic ‘rhythmical’ of the Normalisation period trigger a discussion about cult Czech films?

“Cult film Smoke back in cinemas!” Similar headlines appeared throughout the media before last year’s renewed premiere of Tomáš Vorel’s digitally restored film Smoke (Kouř, 1990). But what does “cult film” mean? Do the authors of such articles even know? Czech media tend to overuse this term in connection to filmmaking. It would also seem that cult films are simply those that show every year on television (particularly during Christmas). But in the case of Smoke, this equation doesn’t apply – it’s not a type of entertainment which an ordinary viewer would look for on television screens during a holiday. And it’s perhaps this very fact that makes it a genuine cult film.

The term cult film belongs to the evolving interdisciplinary field exploring cult cinema combining methods of critical theory, cultural and media studies, sociology and to a certain extent also theology. For its multitude of approaches, this field of film studies is very eclectic and defies set definitions – just like cult films themselves. According to cult cinema theorists Ernest Mathijs and Xavier Mendik, cult films share a certain transgressivity and an ability to cross the boundaries of taste, which they use to gradually attract devoted fans.

Smoke fulfils the criteria of cult cinema more than films like Cosy Dens (Pelíšky, dir. Jan Hřebejk, 1999) and Secluded, Near Woods (Na samotě u lesa, dir. Jiří Menzel, 1976) whose “cult” status is based on popularity and some popular catchphrases. In the following text, I will try to elaborate on that and explain why such “interpretations” of films can be interesting for us.

Influence of political development

Tomáš Vorel began his amateur film career in the late 1970s. At the same time, he got involved with the amateur theatre groups Sklep and Mimóza. The poetics of these then-amateur groups (which he himself helped to form) served as the basis for his student films and his first two non-professional films, Prague Five (Pražská pětka, 1988) and Smoke. During his studies at the Film and TV School of the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague, Vorel made several films with his distinct style and humour – the penultimate one, ING. (1985), explores a clash of a young engineer with an ineffective bureaucratic apparatus. The film innovatively reinterprets the genre conventions of musicals and bases them on rhythmised choric speeches and ironically banal songs – things which later became Smoke’s trademarks.

Towards the end of his studies, motivated by dramaturge Jan Gogola, Vorel, in cooperation with Lumír Tuček from the recitation group Vpřed (Forward), began working on adapting the story of his acclaimed film ING. into a feature film. But the production of Smoke faced difficulties from the start. The initial offer from the Gottwaldov Studios to make a feature film for young audiences was recalled when Vorel and other crew members signed the Několik vět (A Few Sentences) petition and a petition for releasing Václav Havel from prison. A new offer, this time by Barrandov Studio, came more than six months later. When camera tests began, the streets of Prague were stirred by the Velvet Revolution, which affected not only the production process (part of the crew played important roles in the revolution) but also the film’s content. The concept of a “musical of the totalitarian age” emerged from totality at the very moment when Vorel and Tuček had a last chance to rewrite the script. According to Mathijs and Mendik, when the surrounding world interferes with the production or reception of a film, it’s what gives it its cult status. Simply put: “Cult films simply must encounter some difficulties – every time, something interferes with their production, promotion or reception.”[1] From the specifics of the film’s production, one could anticipate the cult potential of the film, which recorded history almost in real time – as a reaction to the political development, some scenes were reshot already during production.

The reception pattern was also affected by the unexpected development. The film, which would have likely caused a sensation before the Velvet Revolution, flopped in cinemas. It attracted less than ten thousand viewers. Right after the Revolution, the audiences were much more interested in Hollywood films or films that were previously banned. But last year’s renewed premiere, just like top positions in various popularity polls, is evidence of a wide fanbase. With its non-traditional reception curve, Smoke resembles many foreign cult films which were initially appreciated only by few fans but managed to acquire a cult following over time.

Changes in Reception

The cult potential of Smoke isn’t rooted just in external events but also in the film’s muddled form. According to Mendik and Mathijs, one of the most important elements of cult films is their ability to blur genre boundaries [2] – cult films are often genre films toying with the conventions of the given genre and reflecting them ironically. Smoke is also a genre film, a musical. But its interpretation and manipulation of this genre is based directly on ING. Vorel labelled both films as “rhythmicals,” a word he made up to describe the invented genre built on rhythmised recitation and musical and dance numbers. The presentation of the film as a representative of a non-existing genre points to its genre unreliability and playfulness.

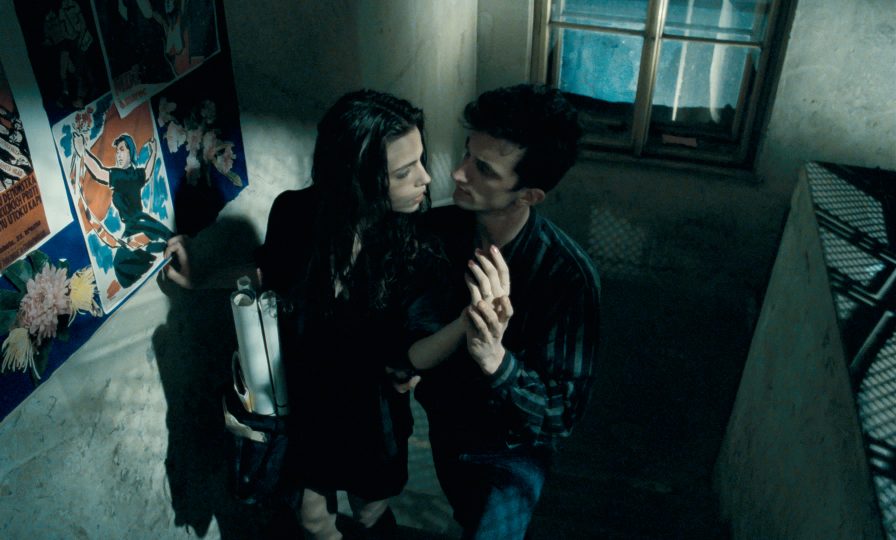

Traditional musical and dance performances in Vorel’s rendition seemingly conform to genre conventions but also subvert them using exaggeration. At first glance ordinary mainstream love duets, ING. parodies contemporary pop music and the genre of romantic musical films. Dance choreography, specific intonation and platitudinal lyrics parody the genre by means of exaggerated pathos bordering on nonsense. The central couple from ING. expresses the euphoria of their love through expressive dance, which transforms into a scooter ride and frolicking in a pool, escalates into hurdling and chariot racing, and peaks at a mass gymnastics event. In another scene, the infatuated engineer sings about defending their love and illustrates the line “my happiness can’t be dismissed, I’ll defend it with my fist” so vigorously to his beloved that she falls to the ground. The duet continues. Similar scenes use devices known from the musical genre to ironize and subvert it.

Smoke has a similar approach but gives more space to ambivalence, which amplifies the film’s cult potential and its appropriation by new audiences. Unlike the intentionally banal tone of ING., the musical numbers in Smoke evoke not only an ironic pleasure stemming in genre subversiveness but (probably despite the authors’ intentions) aim to aesthetically please the viewers. It’s most apparent in the film’s most famous song, Je to fajn. The song of the pompously sleazy cultural official Arnoštěk who was, according to Vorel, supposed to “ridicule Bolshevik discotheques” and star in the “most disgusting and repugnant music video of all times” [3] itself mocks the period discotheques. The authors (music: Michal Vích, lyrics: Lumír Tuček) managed to create a hit with a considerable amount of irony and genuine pleasure that will find its place at many parties even thirty years later, and its choreography can be compared perhaps only to the famous Pulp Fiction dance scene.

For our generation, the attractivity of excessive disco is much more intensive as it has gradually lost its “unpleasantness” and acquired a (sarcastically) nostalgic charm. The very ambivalence of taste formed by imitations of stereotypical genre conventions and cultural phenomena and their exaggerated portrayal, which matures as time goes by, is one of the typical elements of cult cinema. The fact that the reception of Vorel’s Smoke, which offers new enjoyment to new generations, changes over time makes the film a representative of Czech cult cinema.

Ambivalent Ending

Another reason why Smoke didn’t attract so much attention after its premiere can be its – only seldom seen in Czech films – critical reflection of the post-Revolution political development and subversion of the dominant interpretation of history in Czech cinema. While most films portraying the transition to democracy depict the Velvet Revolution as a culmination of history and the story itself, Smoke ironizes this catharsis with a remarkable clairvoyance. Even though at the end of the film evil is knocked down (in the form of one of the characters, literally) and we learn from the roaring that “it’s worth it,” the tone of the closing sequence is far from unambiguous.

While ING. ends with a shot of the main hero looking into the camera and chanting the same chant (which appeared in several theatre performances by the Prague Five), the young engineer in Smoke is the only one not chanting. He lights another cigarette and observes the events in disbelief. While the scene from 1985 appears to be a daring call to action, the 1990 protagonist with a certain dose of scepticism and an amused expression knows that not everything will be sunny in the future. In the scenes which could have been the right material for a sentimental finale, Vorel (quite prophetically for the year 1990) shows the quick coat turning we all witnessed later. While the silent majority led by opportunist totalitarian officials cheers for a rehabilitated dissident, the hero whistles the melody of the film’s soundtrack and knows what’s going to happen. This cheekiness and the ability to ironically reflect even the most revered social and historic events puts Smoke in a solitaire position within Czech cinema and amplifies its cult status.

With its declamatory-musical form, irony and genre subversion, social and ideological norms, Smoke sends an ambiguous message while feeding the viewers exaggeratedly banal and annoying disco hits and moving them with a big happy ending only to have the hero laugh in their faces. This approach corresponds with the attributes of cult films. A comparison with the short film ING. shows the beginnings of a transgressive approach which is later fully developed in Smoke. It also points out the importance of external factors of production and reception which transform the cult potential (apparent already in Vorel’s student films) into a fully-fledged “cult film” status.

We can’t forget the regional dimension of such “cultishness”. The film’s subversiveness and mockery are based on the principles of intertextuality conditioned by domestic context. It is therefore questionable whether the film and its cult status would work to a similar extent outside our historic experience. But this regional specificity makes Smoke an ideal candidate for the perfect example of a Czech cult film.

The question whether it’s important to assess the cult potential of individual films is certainly debatable. With the example of Vorel’s film, I have clearly defined some principles of the cult cinema theory as opposed to the overused term “cult film.” I believe that its cult status secures Smoke a special place in the history of Czechoslovak cinema and can serve as a basis for starting a discussion about Czechoslovak cult cinema.

Notes:

[1] Ernest Mathijs, Xavier Mendik, The Cult Film Reader. London: McGraw-Hill Education 2007, p. 7.

[2] ibid, p. 2.

[3] Tomáš Vorel, Rejža Vorel. Prague: Pražská scéna 2017, p. 135.