The Mystery of the Carpathian Castle (Tajemství hradu v Karpatech, 1981) is a comedy film with an extraordinary sequence of gags, that doesn’t leave the audience with any time to catch their breath from laughter. Yet the last completed film by screenwriter Jiří Brdečka and director Oldřich Lipský was not created with the ease and relaxation that it continues to impress audiences with today. Brdečka was very troubled by the script, no other script had given him such a hard time, and yet he was not satisfied with what was finally produced. This was due both to his health problems, which prevented him from concentrating fully on the creative process, and the nature of the adapted subject.

„It was unexpectedly difficult work“, the writer admitted in an interview for the magazine Záběr.[1] He also described Verne’s novel The Mystery of the Carpathian Castle as very bad, with tediously long expositions and an overabundance of motifs and characters. Above all, however, it was, according to Brdečka, a deadly serious book. In tone, it was the opposite of the intended film, which was supposed to be in the parodic spirit of his two previous collaborations with Lipský – Lemonade Joe (Limonádovy Joe, aneb Koňská opera, 1964) and Adela Has Not Had Her Supper Yet (Adéla ještě nevečeřela, 1978).

The idea of adapting the aforementioned novel by Verne was not particularly new at the turn of the 1970s and 1980s. The Barrandov Studios had been thinking about it at least since 1966, when a completely different film would probably have been produced. Possibly more ornate, as the Italian film entrepreneur Moris Ergas was interested in co-producing it, and more stylized, as the prototype of Verne adaptations at that time were the adventurous special effect films by Karel Zeman An Invention for Destruction (Vynález zkázy, 1958) and The Stolen Airship (Ukradená Vzducholoď, 1966). But The Mystery of the Carpathian Castle remained a back-up dormant project for the case of an emergency. And emergency arose in 1979.

At that time, a space freed up at the Barrandov Studio for one film. To avoid losing the crew, studio and budget, it was necessary to find a substitute subject quickly. It was reportedly Oldřich Lipský who suggested adapting the ignored Verne. Naturally, in the genre of comedy, which was closest to him and which, in addition, the authorities of the nationalized and normalized film industry were relying increasingly more on from the end of the 1970s onwards. Comedy films were supposed to revive and make the anemic domestic production more attractive, to attract more male and female viewers to the cinemas, and therefore they were added to the dramaturgical plans more often.

One of the dramaturgical groups specializing in comedies, or rather more generally in audience favorites, was that of Miloš Brož. Brož’s group preferred films with fantastic themes, wacky comedies and parodies, not the communal satires criticizing the expressions of petty bourgeoisie, which the „rival“ comedy group of Drahoslav Makovička and director Petr Schulhoff were focusing on. Zdeněk Podskalský, Ladislav Rychman, Václav Vorlíček with Miloš Macourek and Lipský with Brdečka carried out their projects with Brož.

Brdečka agreed to Lipský’s proposal to make a Verne adaptation. Perhaps unwisely, but nevertheless with a justified vision of a future mutually enriching collaboration. However, he soon concluded that the novel was not suitable for adapting, let alone to make a film where the audience is supposed to laugh and relax, and that he would have to rearrange the whole plot, change some of the characters and, above all, add humor. After an exhausting process of rewriting, deleting old motifs and adding new ones, Brdečka finally decided to build the plot around opera he enjoyed.

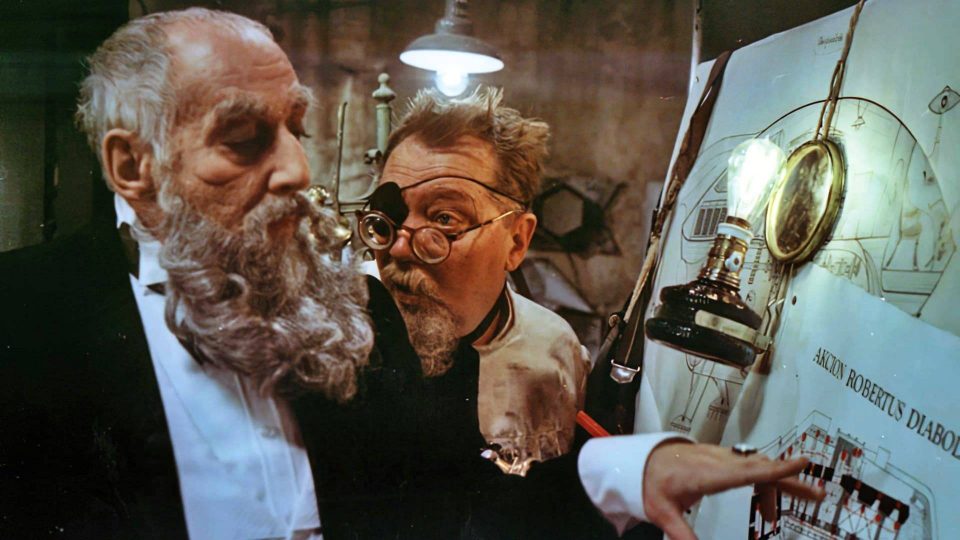

For Brdečka, the main character, Count Felix Teleke of Tölökö (Michal Dočolomanský), is an occasional singer. Thanks to his singing talent, he also met his beloved, the opera diva Salsa Verde (Evelyna Steimarová), who has disappeared off the face of the earth. When staying in Carpathian Mountains, Felix and his faithful butler Ignác (Vlastimil Brodský) catch scent of her trail, they are unaware that it is a trap set by the treacherous Baron Gorce of Gorcena (Miloš Kopecký), who lives in the local castle and coincidentally is also an opera lover. The characters repeatedly find their way to each other through opera, which is also a trigger for memories of their past encounters.

The basic structure of the story otherwise copies Verne’s novel, including the haunted castle, superstitious villagers or a demonic scientist, but Verne’s techno-optimistic visions are parodied by Brdečka’s script without restraint. Similarly, the dismissive Western view of Eastern Europe, common to other classics of the science fiction or horror genre (e.g. the literary Dracula or the cinematic Frankenstein)[2], is also ironized. If nothing else, at least the exoticization of the Romanian countryside amused Brdečka immensely during the writing process.

When he didn’t know what to do with the childishly schematic characters and struggled in vain to come up with another cliché from low literature to spice up the plot, he invented Carpathian folklore with his own dialect mix from Chodenland-Krkonoše-Moravia to distract himself. Surrounded by dictionaries of Czech and Moravian dialects, he put together foreign-sounding words, sentences and lyrics of the marching song of the Carpathian police force, which comes to the rescue at the end of the film. This invented speech was a source of entertainment not only for him, but also his friends.

Brdečka, however, mainly needed to finish writing the script so that filming could begin within the set timeframe. Perhaps because of this time pressure, he simplified his work by taking over the model from Adela. Once again, we have a self-centered lover convinced of his own nobility (and, as in Adela, played by Michal Dočolomanský), a sagacious butler reminiscent of Commissioner Ledvina, and a villain who has failed to work through a past injustice (Miloš Kopecký again).

We are reminded of the earlier collaboration between Brdečka and Lipský by elements of the trashy sweetly painful romance, the evocation of the early era of cinematography (e.g. tinted retrospectives), archaization of speech, updating allusions in words and images, or all sorts of technical achievements brought to life thanks to Jan Švankmajer’s stop-motion animation. Especially the setting is different. The story is not set in Prague at the beginning of the twentieth century, but in the forests, mountains and the castle in the title.

The filming, about the process of which we do not have detailed information, took place in 1980 in Čachtice, Slovakia (Baron Gorc is hiding in the ruins of the castle there), in the open-air folk architecture museum in Rožnov pod Radhoštěm (the village of Vyšné Vlkodlaky), but also in Český ráj, Petřín, Vyšehrad, the Kinský Garden and the Stromovka Park. The interiors were shot at the beginning of 1981 in Barrandov, in a set designed by architect Vladimír Labský.

But Brdečka did not just quote himself in The Mystery of the Carpathian Castle. The references to popular genres and other works relying on the attractiveness of the folklore world of superstitions are so frequent and obvious that a new quality is born out of this eclecticism and mimicry. The exaggerated visual stylization, the overacting of the actors and the repetition of jokes that are too numerous for the simple narrative structure to bear, as well as the fragmentation of the plot into many scenes (which bothered the critics and also Brdečka himself [3]) are the reasons why the film became iconic for so many viewers.

As we all know, in order for cult films to hold a specific place in the audience’s memory, it is not necessary that they hold together flawlessly and are narratively fluent, with one scene seamlessly following another, but instead that they offer enough highlights that they continue to fulfil their (entertaining) function even when removed from their original context. In The Mystery of the Carpathian Castle, there are lots of them. From a folding motorized scooter and other „interesting folkloristic objects“ to a Cimrmanian play on words („There is not even a scrap left of the Devil’s Castle“) to a bloody finale.

Jiří Brdečka died nine months after the film’s premiere. He was no longer able to work on the sequel to Adela, carrying the working title Nick Carter in Istanbul, and he was not even able to complete the scene sequences for Lipský’s The Three Veterans. It was one of the main cimrmanologists, Zdeněk Svěrák, who naturally followed Brdečka’s tradition of playful, childishly mischievous, yet very intelligent humor, who finalised the script.

The Mystery of the Carpathian Castle (Czechoslovakia, 1981), director: Oldřich Lipský, script: Jiří Brdečka, Oldřich Lipský, cinematography: Viktor Růžička, editing: Miroslav Hájek, music: Luboš Fišer, cast: Michal Dočolomanský, Jan Hartl, Miloš Kopecký, Rudolf Hrušínský, Vlastimil Brodský, Evelyna Steimarová, Augustín Kubán, Jaroslava Kretschmerová et al. Barrandov Film Studios, 97 min.

Literature:

Tereza Brdečková, Jiří Brdečka. Prague: Arbor vitae 2013.

Tereza Brdečková, Lukáš Skupa, Tajemství hradu v Karpatech & Jiří Brdečka. Prague: Limonádový Joe 2018.

Štěpán Hulík, Kinematografie zapomnění. Počátky normalizace ve Filmovém studiu Barrandov (1968–1973). Prague: Academia 2011.

Milena Nyklová, Tajemství hradu v Karpatech aneb O parodii s Jiřím Brdečkou. Záběr 14, 1981, no. 12, p. 3.

Alexandra Prosnicová, Tajemství hradu v Karpatech. Kino 36, 1981, no. 13, pp. 8–9.

Ladislava Vydrová, Tajemný hrad v Karpatech. Záběr 14, 1981, no. 2, p. 3.

Notes:

[1] Milena Nyklová, Tajemství hradu v Karpatech aneb O parodii s Jiřím Brdečkou. Záběr 14, 1981, no. 12, p. 3.

[2] „Additionally, I was inspired by old Hollywood films such as Frankenstein or The Merry Widow, in which it was the depiction of Austrian folklore that made one smile,“ Brdečka revealed in a contemporary interview. Alexandra Prosnicová, Tajemství hradu v Karpatech. Kino 36, 1981, no. 13, p. 9.

[3] Tereza Brdečková, Jiří Brdečka. Prague: Arbor vitae 2013, p. 64.